The Hartford 2007 Annual Report Download - page 36

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 36 of the 2007 The Hartford annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. 36

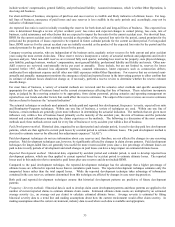

The advantage of frequency / severity techniques is that frequency estimates are generally easier to predict and external information can

be used to supplement internal data in making severity estimates.

Expected Loss Ratio method. Loss ratios for prior accident years are used to determine the appropriate expected loss ratio for the current

accident year after applying anticipated changes in rates, pricing and loss costs. The current accident year expected loss ratio is

multiplied by earned premium to calculate estimated ultimate losses.

Expected loss ratio techniques are useful for early periods of maturity on long-tailed lines of business, where very little paid or reported

loss information is available.

Bornhuetter-Ferguson method. This method is a combination of the expected loss ratio method and the reported development method,

where the reported loss development method is given more weight as an accident year matures.

Berquist-Sherman method. This method is used in cases where historical development patterns may be inappropriate for use in

estimating ultimate losses of recent accident years. Under this method, the pattern of historical reported losses is adjusted for changes in

case reserve adequacy and the pattern of historical paid losses is adjusted for changes in claim settlement rates.

For all lines of business, variations of the above methods are used. Examples of variation within the paid and reported development

methods include:

• The accident period used may vary (e.g., year, quarter, or month)

• The Company may analyze the data by coverage (e.g., bodily injury separate from property damage)

• There may be adjustments for unusual loss activity

• For ALAE, the Company uses patterns of the relationship between paid ALAE and paid losses.

Examples of variation within the frequency /severity methods include:

• For one sub-set of professional liability business, management estimates frequency, not through historical claim count

development, but through an analysis of the securities class actions filed and policy listings

• For some methods, management projects severity on only open claims

• In the commercial liability lines, the Company performs the frequency / severity technique only on claims over a certain size

• For ALAE, the Company analyzes ALAE on claims in suit and associated legal expenses separately from ALAE on other claims.

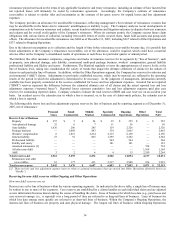

For each line of business, certain methods are given more influence than other methods. The discussion below gives a general

indication of which methods are preferred by line of business. Because the actuarial estimates are generated at a much finer level of

detail than line of business (e.g., by distribution channel, coverage, accident period), this description should not be assumed to apply to

each coverage and accident year within a line of business. Also, as circumstances change, the methods that are given more influence

will change. For example, for Personal Lines auto liability claims, reported development techniques are currently given less emphasis in

making estimates for recent accident years because case reserving practices have been changing in the recent past. If case reserving

practices become more stable, reported development techniques may be given more weight.

Property and Auto Physical Damage. These lines are fast-developing and paid and reported development techniques are used. The

Company performs and relies primarily on reported development techniques and frequency/severity and Bornhuetter-Ferguson

techniques for the most immature accident months.

Auto Liability – Personal Lines. For auto liability, and bodily injury in particular, the Company performs a greater number of

techniques than it does for property and auto physical damage, including paid and reported development methods, frequency/severity

approaches, and Berquist-Sherman techniques. The Company generally uses the reported development method for older accident years

and the frequency/severity and Berquist-Sherman methods for more recent accident years. Recent periods are heavily influenced by

changes in case reserve practices and changing disposal rates; the frequency/severity techniques are not affected as much by these

changes and the Berquist-Sherman techniques specifically adjust for changes in case reserve adequacy and claim disposal rates.

Auto Liability – Commercial Lines, Package Business and Short-Tailed General Liability. As with Personal Lines auto liability, the

Company performs a variety of techniques, including the paid and reported development methods and frequency / severity techniques.

For older, more mature accident years, management finds that reported development techniques are best. For more recent accident

years, management typically prefers frequency / severity techniques that allow it to make assumptions about the frequency of larger

claims.

Long-Tailed General Liability, Fidelity and Surety and Large Deductible Workers’ Compensation. For these very long-tailed lines of

business, the Company generally relies on the expected loss ratio, Bornhuetter-Ferguson and reported development techniques.

Management generally weights these techniques together, relying more heavily on the expected loss ratio method at early ages of

development and more on the reported development method as an accident year matures.

Workers’ Compensation. Workers’ compensation is the Company’ s single largest reserve line of business and management does the

largest amount of actuarial analysis on this line of business. Methods performed include paid and reported development, variations on

expected loss ratio methods, and an in-depth analysis on the largest states. Paid development patterns are historically very stable in the

Company’s workers’ compensation business, so paid techniques are preferred for older accident periods. For more recent periods, paid

techniques are less predictive of the ultimate liability since such a low percentage of ultimate losses are paid in early periods of