The Hartford 2007 Annual Report Download - page 38

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 38 of the 2007 The Hartford annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. 38

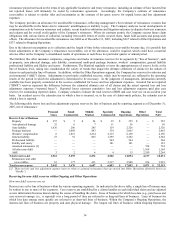

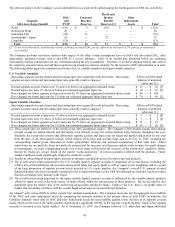

In the Specialty Commercial segment, many lines of insurance, such as excess insurance and large deductible workers’ compensation

insurance are “long-tail” lines of insurance. For long-tail lines, the period of time between the incidence of the insured loss and either

the reporting of the claim to the insurer, the settlement of the claim, or the payment of the claim can be substantial, and in some cases,

several years. As a result of this extended period of time for losses to emerge, reserve estimates for these lines are more uncertain (i.e.,

more variable) than reserve estimates for shorter-tail lines of insurance. Estimating required reserve levels for large deductible workers’

compensation insurance is further complicated by the uncertainty of whether losses that are attributable to the deductible amount will be

paid by the insured; if such losses are not paid by the insured due to financial difficulties, the Company would be contractually liable.

Another example of reserve variability relates to reserves for directors and officers insurance. There is potential volatility in the

required level of reserves due to the continued uncertainty regarding the number and severity of class action suits, including uncertainty

regarding the Company’ s exposure to losses arising from the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market. Additionally, the Company’ s

exposure to losses under directors and officers insurance policies is in excess layers, making estimates of loss more complex.

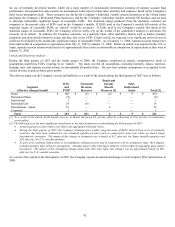

Impact of changes in key assumptions on reserve volatility

As stated above, the Company’ s practice is to estimate reserves using a variety of methods, assumptions and data elements. Within its

reserve estimation process for reserves other than asbestos and environmental, the Company does not derive statistical loss distributions

or confidence levels around its reserve estimate and, as a result, does not have reserve range estimates to disclose.

The reserve estimation process includes explicit assumptions about a number of factors in the internal and external environment. Across

most lines of business, the most important assumptions are future loss development factors applied to paid or reported losses to date.

For most lines, the reported loss development factor is most important. In workers’ compensation, paid loss development factors are

also important. The trend in loss costs is also a key assumption, particularly in the most recent accident years, where loss development

factors are less credible.

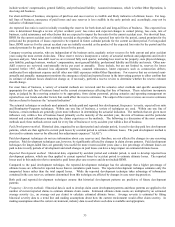

The following discussion includes disclosure of possible variation from current estimates of loss reserves due to a change in certain key

assumptions. Each of the impacts described below is estimated individually, without consideration for any correlation among key

assumptions or among lines of business. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to take each of the amounts described below and add them

together in an attempt to estimate volatility for the Company’ s reserves in total. The estimated variation in reserves due to changes in

key assumptions is a reasonable estimate of possible variation that may occur in the future, likely over a period of several calendar

years. It is important to note that the variation discussed is not meant to be a worst-case scenario, and therefore, it is possible that future

variation may be more than the amounts discussed below.

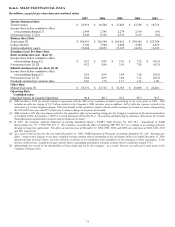

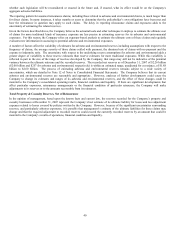

Recorded reserves for workers’ compensation, net of reinsurance, are $6.2 billion in total for Ongoing Operations. The two most

important assumptions for workers’ compensation reserves are loss development factors and loss cost trends, particularly medical cost

inflation. Loss development patterns are dependent on medical cost inflation. Approximately half of the workers’ compensation net

reserves are related to future medical costs. A review of National Council on Compensation Insurance (“NCCI”) data suggests that the

annual growth in industry medical claim costs has varied from -2% to +12% since 1991. This data shows that medical inflation has

been highly variable over the past decade. Across the entire workers’ compensation reserve base, a 1 point change in the annual medical

inflation rate would change the estimated net reserve by $650, in either direction.

Recorded reserves for auto liability, net of reinsurance, are $2.3 billion across all lines, $1.6 billion of which is in Personal Lines.

Personal auto liability reserves are shorter-tailed than other lines of business (such as workers’ compensation) and, therefore, less

volatile. However, the size of the reserve base means that future changes in estimates could be material to the Company’ s results of

operations in any given period. The key assumption for Personal Lines auto liability is the annual loss cost trend, particularly the

severity trend component of loss costs. A review of Insurance Services Office (“ISO”) data suggests that annual growth in industry

severity since 1999 has varied from +1% to +6%. The ISO data shows recent severity changes to be in the middle of this range. A 2.5

point change in assumed annual severity is within historical variation for the industry and for the Company. A 2.5 point change in

assumed annual severity for the two most recent accident years would change the estimated net reserve need by $90, in either direction.

Assumed annual severity for accident years prior to the two most recent accident years is likely to have minimal variability.

Recorded reserves for general liability, net of reinsurance, are $2.4 billion across Small Commercial, Middle Market and Specialty

Commercial. Reported loss development patterns are a key assumption for this line of business, particularly for more mature accident

years. Historically, assumptions on reported loss development patterns have been impacted by, among other things, emergence of new

types of claims (e.g., construction defect claims) or a shift in the mixture between smaller, more routine claims and larger, more

complex claims. The Company has reviewed the historical variation in reported loss development patterns. If the reported loss

development patterns change by 10%, the estimated net reserve need would change by $350, in either direction. A 10% change in

reported loss development patterns is within historical variation, as measured by the variation around the average development factors as

reported in statutory accident year reports.

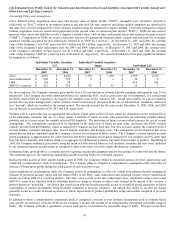

Similar to general liability, assumed casualty reinsurance is affected by reported loss development pattern assumptions. In addition to

the items identified above that would affect both direct and reinsurance liability claim development patterns, there is also an impact to

assumed reporting patterns for any changes in claim notification from ceding companies to the reinsurer. Recorded net reserves for

HartRe assumed reinsurance business, excluding asbestos and environmental liabilities, within Other Operations were $724 as of

December 31, 2007. If the reported loss development patterns underlying the Company's net reserves for HartRe assumed casualty

reinsurance change by 10%, the estimated net reserve need would change by $250, in either direction. A 10% change in reported loss