IBM 2003 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 2003 IBM annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

7

Becoming one is dauntingly hard to pull off. It

requires both the end-to-end integration of the tech-

nology—which niche product vendors simply cannot

do—and the integration of technology with business

processes. This in turn requires deep business knowl-

edge and industry expertise that few traditional

technology companies have, and significant technical

knowledge and research strengths that few consulting

firms possess.

Integration is also an emerging force in core tech-

nology and computing architectures. To cite one

example, advances in semiconductor devices have

been largely propelled by increasing the clock speed

of the microprocessor chip; this is like revving up the

RPM of a car engine. But while advances in raw speed

are continuing apace, they are no longer enough to

increase chip and overall system performance. For one

thing, chips have become so densely packed with

transistors that they produce more heat than can be

cost-effectively dissipated.

The solution is integration—putting multiple, often

less-than-top-speed processors on the same chip, along

with additional functions like fast memory and high-

performance input/output. This is the approach IBM

engineers have taken in developing our Blue Gene

supercomputer. Integration of this sophistication is

beyond the reach of most chip and systems companies.

It requires expertise not just in semiconductors but

in advanced systems architecture, custom logic

design, operating systems and software tools. This

is the kind of expertise that IBM has built up over

decades, and it is not easily replicated. And that’s

why technology leaders like Sony, Cisco, Apple and

QUALCOMM have partnered with IBM for advanced

technology—and why last year Microsoft licensed

IBM’s microprocessor technology for use in its

next-generation Xbox game console.

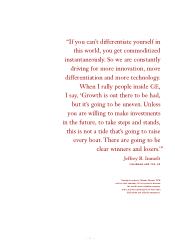

Bulking up in on demand

Many IT companies will struggle with this world that

is dawning—with the need to choose between open

and proprietary, between serving consumers and

enterprises, between redistributing other people’s

intellectual capital and innovating. This is not about

making pronouncements or promises. A company

cannot be all things to every client, every partner

and every investor.

For our part, we’ve decided. The two parallel trajec-

tories of integration—in client demand and in what the

technology requires—play directly to IBM’s historic

strengths. However, even with everything IBM brought

to this table, we needed more. That’s why we’ve made

acquisitions such as PricewaterhouseCoopers

Consulting (PwCC), Rational software and 19 other

companies in the past two years. And it’s why we reset

our priorities in R&D to develop more technologies

and services specifically for client needs in the

on demand era.

On demand integration is also why we’ve placed a

huge bet on standards, from the Internet protocols

and Linux to grid computing and Web services.

Without open technical interfaces and agreed-upon

standards, even integration within a single enterprise

would remain a gargantuan task. And forget about

integration with the other companies, business

processes, applications, pervasive computing devices,

laws, regulations, customs and cultures that make up

the ever-more-global marketplace of the 21st century.

An IT company’s position on open standards—not

just its rhetoric, but its actions—is a clear indicator

of whether it faces forward or backward, is serving

the needs of clients or protecting its market position.

In addition to the opportunities I’ve described, our

move into on demand has opened up some very large

businesses beyond the frontiers of the traditional IT

industry—opportunities that remain out of reach for

most of our competitors.

One promising example is Business Transformation

Outsourcing (BTO), which was not even part of the

industry lexicon 18 months ago. In BTO engagements,

IBM becomes responsible for transforming—and

actually providing—a client’s business process in

areas such as human resources, procurement, customer

care, and finance and administration. Thanks to the

acquisition of PwCC and the formation of IBM

Business Consulting Services, we generated nearly

$3 billion in BTO signings during the fourth quarter of

2003 alone. To give a rough idea of the potential here,

the current size of businesses’ outsourced spending on

sales, marketing, logistics, finance, HR and all other

administrative processes is about $1 trillion a year. Of

that, there is an opportunity in excess of $1oo billion

in the BTO areas we are pursuing. We are committed

to extend our leadership position in BTO in 2004.

CHAIRMAN’S LETTER