Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Annual Report Download - page 19

Download and view the complete annual report

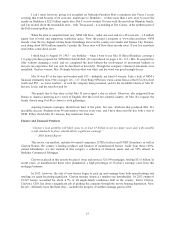

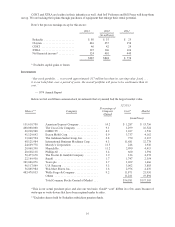

Please find page 19 of the 2013 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Berkshire has one major equity position that is not included in the table: We can buy 700 million shares of

Bank of America at any time prior to September 2021 for $5 billion. At yearend these shares were worth $10.9

billion. We are likely to purchase the shares just before expiration of our option. In the meantime, it is important for

you to realize that Bank of America is, in effect, our fifth largest equity investment and one we value highly.

In addition to our equity holdings, we also invest substantial sums in bonds. Usually, we’ve done well in

these. But not always.

Most of you have never heard of Energy Future Holdings. Consider yourselves lucky; I certainly wish I

hadn’t. The company was formed in 2007 to effect a giant leveraged buyout of electric utility assets in Texas. The

equity owners put up $8 billion and borrowed a massive amount in addition. About $2 billion of the debt was

purchased by Berkshire, pursuant to a decision I made without consulting with Charlie. That was a big mistake.

Unless natural gas prices soar, EFH will almost certainly file for bankruptcy in 2014. Last year, we sold

our holdings for $259 million. While owning the bonds, we received $837 million in cash interest. Overall,

therefore, we suffered a pre-tax loss of $873 million. Next time I’ll call Charlie.

A few of our subsidiaries – primarily electric and gas utilities – use derivatives in their operations.

Otherwise, we have not entered into any derivative contracts for some years, and our existing positions continue to

run off. The contracts that have expired have delivered large profits as well as several billion dollars of medium-

term float. Though there are no guarantees, we expect a similar result from those remaining on our books.

Some Thoughts About Investing

Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike.

—The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham

It is fitting to have a Ben Graham quote open this discussion because I owe so much of what I know about

investing to him. I will talk more about Ben a bit later, and I will even sooner talk about common stocks. But let me

first tell you about two small non-stock investments that I made long ago. Though neither changed my net worth by

much, they are instructive.

This tale begins in Nebraska. From 1973 to 1981, the Midwest experienced an explosion in farm prices,

caused by a widespread belief that runaway inflation was coming and fueled by the lending policies of small rural

banks. Then the bubble burst, bringing price declines of 50% or more that devastated both leveraged farmers and

their lenders. Five times as many Iowa and Nebraska banks failed in that bubble’s aftermath than in our recent

Great Recession.

In 1986, I purchased a 400-acre farm, located 50 miles north of Omaha, from the FDIC. It cost me

$280,000, considerably less than what a failed bank had lent against the farm a few years earlier. I knew nothing

about operating a farm. But I have a son who loves farming and I learned from him both how many bushels of corn

and soybeans the farm would produce and what the operating expenses would be. From these estimates, I

calculated the normalized return from the farm to then be about 10%. I also thought it was likely that productivity

would improve over time and that crop prices would move higher as well. Both expectations proved out.

I needed no unusual knowledge or intelligence to conclude that the investment had no downside and

potentially had substantial upside. There would, of course, be the occasional bad crop and prices would sometimes

disappoint. But so what? There would be some unusually good years as well, and I would never be under any

pressure to sell the property. Now, 28 years later, the farm has tripled its earnings and is worth five times or more

what I paid. I still know nothing about farming and recently made just my second visit to the farm.

17