Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Annual Report Download - page 10

Download and view the complete annual report

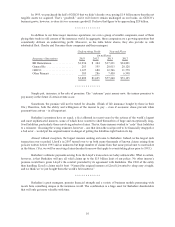

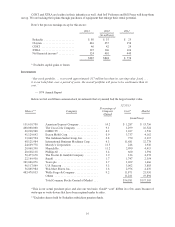

Please find page 10 of the 2013 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit

that adds to the investment income our float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free

money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it.

Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous

in most years that it causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in

effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. For example, State Farm, by far the country’s largest insurer and a

well-managed company besides, incurred an underwriting loss in nine of the twelve years ending in 2012 (the latest

year for which their financials are available, as I write this). Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the

insurance industry – despite the float income all companies enjoy – will continue its dismal record of earning

subnormal returns as compared to other businesses.

As noted in the first section of this report, we have now operated at an underwriting profit for eleven

consecutive years, our pre-tax gain for the period having totaled $22 billion. Looking ahead, I believe we will

continue to underwrite profitably in most years. Doing so is the daily focus of all of our insurance managers who

know that while float is valuable, it can be drowned by poor underwriting results.

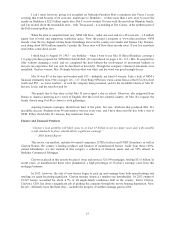

So how does our float affect intrinsic value? When Berkshire’s book value is calculated, the full amount of

our float is deducted as a liability, just as if we had to pay it out tomorrow and could not replenish it. But to think of

float as strictly a liability is incorrect; it should instead be viewed as a revolving fund. Daily, we pay old claims –

some $17 billion to more than five million claimants in 2013 – and that reduces float. Just as surely, we each day

write new business and thereby generate new claims that add to float. If our revolving float is both costless and

long-enduring, which I believe it will be, the true value of this liability is dramatically less than the accounting

liability.

A counterpart to this overstated liability is $15.5 billion of “goodwill” that is attributable to our insurance

companies and included in book value as an asset. In very large part, this goodwill represents the price we paid for

the float-generating capabilities of our insurance operations. The cost of the goodwill, however, has no bearing on

its true value. For example, if an insurance business sustains large and prolonged underwriting losses, any goodwill

asset carried on the books should be deemed valueless, whatever its original cost.

Fortunately, that does not describe Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our

insurance goodwill – what we would happily pay to purchase an insurance operation possessing float of similar

quality to that we have – to be far in excess of its historic carrying value. The value of our float is one reason – a

huge reason – why we believe Berkshire’s intrinsic business value substantially exceeds its book value.

************

Berkshire’s attractive insurance economics exist only because we have some terrific managers running

disciplined operations that possess strong, hard-to-replicate business models. Let me tell you about the major units.

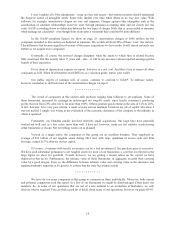

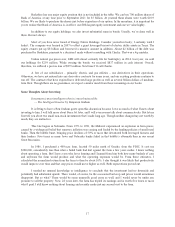

First by float size is the Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group, managed by Ajit Jain. Ajit insures risks

that no one else has the desire or the capital to take on. His operation combines capacity, speed, decisiveness and,

most important, brains in a manner unique in the insurance business. Yet he never exposes Berkshire to risks that

are inappropriate in relation to our resources. Indeed, we are far more conservative in avoiding risk than most large

insurers. For example, if the insurance industry should experience a $250 billion loss from some mega-

catastrophe – a loss about triple anything it has ever experienced – Berkshire as a whole would likely record a

significant profit for the year because of its many streams of earnings. And we would remain awash in cash,

looking for large opportunities if the catastrophe caused markets to go into shock. All other major insurers and

reinsurers would meanwhile be far in the red, with some facing insolvency.

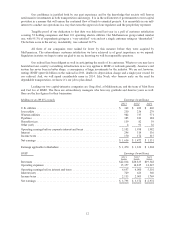

From a standing start in 1985, Ajit has created an insurance business with float of $37 billion and a large

cumulative underwriting profit, a feat no other insurance CEO has come close to matching. Ajit’s mind is an idea

factory that is always looking for more lines of business he can add to his current assortment.

8