UPS 2011 Annual Report Download - page 67

Download and view the complete annual report

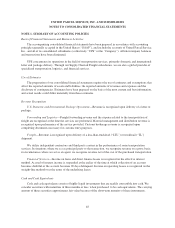

Please find page 67 of the 2011 UPS annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Ongoing expense will increase in 2012 compared with 2011, due primarily to the decline in the U.S.

discount rate used to determine expense from 5.95% for 2011 to 5.61% for 2012. This is partially offset by the

contributions to the plans in 2011 that increased the expected return on assets used for expense calculation

purposes.

Depreciation, Residual Value and Impairment of Fixed Assets

As of December 31, 2011, we had $17.621 billion of net fixed assets, the most significant category of which

is aircraft. In accounting for fixed assets, we make estimates about the expected useful lives and the expected

residual values of the assets, and the potential for impairment based on the fair values of the assets and the cash

flows generated by these assets.

In estimating the lives and expected residual values of aircraft, we have relied upon actual experience with

the same or similar aircraft types. Subsequent revisions to these estimates could be caused by changes to our

maintenance program, changes in the utilization of the aircraft, governmental regulations on aging aircraft and

changing market prices of new and used aircraft of the same or similar types. We periodically evaluate these

estimates and assumptions, and adjust the estimates and assumptions as necessary. Adjustments to the expected

lives and residual values are accounted for on a prospective basis through depreciation expense.

We review long-lived assets for impairment when circumstances indicate the carrying amount of an asset

may not be recoverable based on the undiscounted future cash flows of the asset. If the carrying amount of the

asset is determined not to be recoverable, a write-down to fair value is recorded. Fair values are determined based

on quoted market values, discounted cash flows or external appraisals, as applicable. We review long-lived assets

for impairment at the individual asset or the asset group level for which the lowest level of independent cash

flows can be identified. The circumstances that would indicate potential impairment may include, but are not

limited to, a significant change in the extent to which an asset is utilized, a significant decrease in the market

value of an asset and operating or cash flow losses associated with the use of the asset. In estimating cash flows,

we project future volume levels for our different air express products in all geographic regions in which we do

business. Adverse changes in these volume forecasts, or a shortfall of our actual volume compared with our

projections, could result in our current aircraft capacity exceeding current or projected demand. This situation

would lead to an excess of a particular aircraft type, resulting in an aircraft impairment charge or a reduction of

the expected life of an aircraft type (thus resulting in increased depreciation expense).

In 2011 and 2010, there were no indicators of impairment in our aircraft fleet, and no impairment charges

were recorded in either period. In 2009, we recorded a $181 million impairment charge, as described in the

following paragraphs.

In 2008, we had announced that we were in negotiations with DHL to provide air transportation services for

all of DHL’s express, deferred and international package volume within the United States, as well as air

transportation services between the United States, Canada and Mexico. In early April 2009, UPS and DHL

mutually agreed to terminate further discussions on providing these services. Additionally, our U.S. Domestic

Package air delivery volume had declined for several quarters as a result of persistent economic weakness and

shifts in product mix from our premium air services to our lower cost ground services. As a result of these

factors, the utilization of certain aircraft fleet types had declined and was expected to be lower in the future.

Based on the factors noted above, as well as FAA aging aircraft directives that would require significant

future maintenance expenditures, we determined that a triggering event had occurred that required an impairment

assessment of our McDonnell-Douglas DC-8-71 and DC-8-73 aircraft fleets. We conducted an impairment

analysis as of March 31, 2009, and determined that the carrying amount of these fleets was not recoverable due to

the accelerated expected retirement dates of the aircraft. Based on anticipated residual values for the airframes,

engines, and parts, we recognized an impairment charge of $181 million in the first quarter of 2009. The DC-8

fleets were subsequently retired from service.

55