Berkshire Hathaway 2011 Annual Report Download - page 8

Download and view the complete annual report

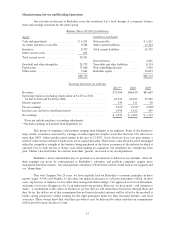

Please find page 8 of the 2011 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.We’ve regularly emphasized that our book-value performance is almost certain to outpace the S&P 500

in a bad year for the stock market and just as certainly will fall short in a strong up-year. The test is how we do

over time. Last year’s annual report included a table laying out results for the 42 five-year periods since we took

over at Berkshire in 1965 (i.e., 1965-69, 1966-70, etc.). All showed our book value beating the S&P, and our

string held for 2007-11. It will almost certainly snap, though, if the S&P 500 should put together a five-year

winning streak (which it may well be on its way to doing as I write this).

************

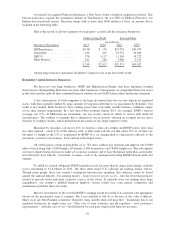

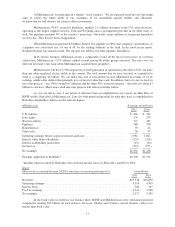

I also included two tables last year that set forth the key quantitative ingredients that will help you

estimate our per-share intrinsic value. I won’t repeat the full discussion here; you can find it reproduced on

pages 99-100. To update the tables shown there, our per-share investments in 2011 increased 4% to $98,366, and

our pre-tax earnings from businesses other than insurance and investments increased 18% to $6,990 per share.

Charlie and I like to see gains in both areas, but our primary focus is on building operating earnings. Over

time, the businesses we currently own should increase their aggregate earnings, and we hope also to purchase some

large operations that will give us a further boost. We now have eight subsidiaries that would each be included in the

Fortune 500 were they stand-alone companies. That leaves only 492 to go. My task is clear, and I’m on the prowl.

Share Repurchases

Last September, we announced that Berkshire would repurchase its shares at a price of up to 110% of book

value. We were in the market for only a few days – buying $67 million of stock – before the price advanced beyond

our limit. Nonetheless, the general importance of share repurchases suggests I should focus for a bit on the subject.

Charlie and I favor repurchases when two conditions are met: first, a company has ample funds to take

care of the operational and liquidity needs of its business; second, its stock is selling at a material discount to the

company’s intrinsic business value, conservatively calculated.

We have witnessed many bouts of repurchasing that failed our second test. Sometimes, of course,

infractions – even serious ones – are innocent; many CEOs never stop believing their stock is cheap. In other

instances, a less benign conclusion seems warranted. It doesn’t suffice to say that repurchases are being made to

offset the dilution from stock issuances or simply because a company has excess cash. Continuing shareholders

are hurt unless shares are purchased below intrinsic value. The first law of capital allocation – whether the

money is slated for acquisitions or share repurchases – is that what is smart at one price is dumb at another. (One

CEO who always stresses the price/value factor in repurchase decisions is Jamie Dimon at J.P. Morgan; I

recommend that you read his annual letter.)

Charlie and I have mixed emotions when Berkshire shares sell well below intrinsic value. We like

making money for continuing shareholders, and there is no surer way to do that than by buying an asset – our

own stock – that we know to be worth at least x for less than that – for .9x, .8x or even lower. (As one of our

directors says, it’s like shooting fish in a barrel, after the barrel has been drained and the fish have quit flopping.)

Nevertheless, we don’t enjoy cashing out partners at a discount, even though our doing so may give the selling

shareholders a slightly higher price than they would receive if our bid was absent. When we are buying,

therefore, we want those exiting partners to be fully informed about the value of the assets they are selling.

At our limit price of 110% of book value, repurchases clearly increase Berkshire’s per-share intrinsic

value. And the more and the cheaper we buy, the greater the gain for continuing shareholders. Therefore, if given

the opportunity, we will likely repurchase stock aggressively at our price limit or lower. You should know,

however, that we have no interest in supporting the stock and that our bids will fade in particularly weak markets.

Nor will we buy shares if our cash-equivalent holdings are below $20 billion. At Berkshire, financial strength

that is unquestionable takes precedence over all else.

************

This discussion of repurchases offers me the chance to address the irrational reaction of many investors

to changes in stock prices. When Berkshire buys stock in a company that is repurchasing shares, we hope for two

events: First, we have the normal hope that earnings of the business will increase at a good clip for a long time to

come; and second, we also hope that the stock underperforms in the market for a long time as well. A corollary to

this second point: “Talking our book” about a stock we own – were that to be effective – would actually be

harmful to Berkshire, not helpful as commentators customarily assume.

6