Berkshire Hathaway 2011 Annual Report Download - page 10

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 10 of the 2011 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

Insurance

Let’s look first at insurance, Berkshire’s core operation and the engine that has propelled our expansion

over the years.

Property-casualty (“P/C”) insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases,

such as those arising from certain workers’ compensation accidents, payments can stretch over decades. This

collect-now, pay-later model leaves us holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to

others. Meanwhile, we get to invest this float for Berkshire’s benefit. Though individual policies and claims

come and go, the amount of float we hold remains remarkably stable in relation to premium volume.

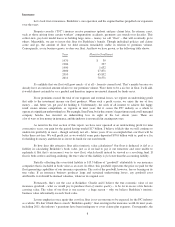

Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float. And how we have grown, as the following table shows:

Year Float (in $ millions)

1970 $ 39

1980 237

1990 1,632

2000 27,871

2010 65,832

2011 70,571

It’s unlikely that our float will grow much – if at all – from its current level. That’s mainly because we

already have an outsized amount relative to our premium volume. Were there to be a decline in float, I will add,

it would almost certainly be very gradual and therefore impose no unusual demand for funds on us.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit

that adds to the investment income our float produces. When such a profit occurs, we enjoy the use of free

money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it. Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy

result creates intense competition, so vigorous in most years that it causes the P/C industry as a whole to

operate at a significant underwriting loss. For example, State Farm, by far the country’s largest insurer and a well-managed

company besides, has incurred an underwriting loss in eight of the last eleven years. There are

a lot of ways to lose money in insurance, and the industry is resourceful in creating new ones.

As noted in the first section of this report, we have now operated at an underwriting profit for nine

consecutive years, our gain for the period having totaled $17 billion. I believe it likely that we will continue to

underwrite profitably in most – though certainly not all – future years. If we accomplish that, our float will be

better than cost-free. We will profit just as we would if some party deposited $70.6 billion with us, paid us a fee

for holding its money and then let us invest its funds for our own benefit.

So how does this attractive float affect intrinsic value calculations? Our float is deducted in full as a

liability in calculating Berkshire’s book value, just as if we had to pay it out tomorrow and were unable to

replenish it. But that’s an incorrect way to view float, which should instead be viewed as a revolving fund. If

float is both costless and long-enduring, the true value of this liability is far lower than the accounting liability.

Partially offsetting this overstated liability is $15.5 billion of “goodwill” attributable to our insurance

companies that is included in book value as an asset. In effect, this goodwill represents the price we paid for the

float-generating capabilities of our insurance operations. The cost of the goodwill, however, has no bearing on its

true value. If an insurance business produces large and sustained underwriting losses, any goodwill asset

attributable to it should be deemed valueless, whatever its original cost.

Fortunately, that’s not the case at Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our

insurance goodwill – what we would pay to purchase float of similar quality – to be far in excess of its historic

carrying value. The value of our float is one reason – a huge reason – why we believe Berkshire’s intrinsic

business value substantially exceeds book value.

Let me emphasize once again that cost-free float is not an outcome to be expected for the P/C industry

as a whole: We don’t think there is much “Berkshire-quality” float existing in the insurance world. In most years,

including 2011, the industry’s premiums have been inadequate to cover claims plus expenses. Consequently, the

8