Berkshire Hathaway 2011 Annual Report Download - page 6

Download and view the complete annual report

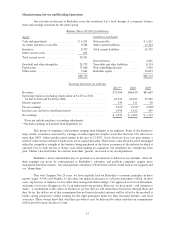

Please find page 6 of the 2011 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.• In total, our entire string of operating companies spent $8.2 billion for property, plant and equipment in

2011, smashing our previous record by more than $2 billion. About 95% of these outlays were made in

the U.S., a fact that may surprise those who believe our country lacks investment opportunities. We

welcome projects abroad, but expect the overwhelming majority of Berkshire’s future capital

commitments to be in America. In 2012, these expenditures will again set a record.

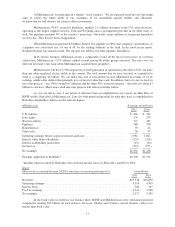

• Our insurance operations continued their delivery of costless capital that funds a myriad of other

opportunities. This business produces “float” – money that doesn’t belong to us, but that we get to

invest for Berkshire’s benefit. And if we pay out less in losses and expenses than we receive in

premiums, we additionally earn an underwriting profit, meaning the float costs us less than nothing.

Though we are sure to have underwriting losses from time to time, we’ve now had nine consecutive

years of underwriting profits, totaling about $17 billion. Over the same nine years our float increased

from $41 billion to its current record of $70 billion. Insurance has been good to us.

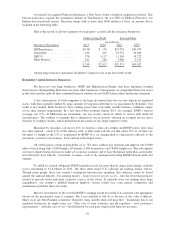

• Finally, we made two major investments in marketable securities: (1) a $5 billion 6% preferred stock of

Bank of America that came with warrants allowing us to buy 700 million common shares at $7.14 per

share any time before September 2, 2021; and (2) 63.9 million shares of IBM that cost us $10.9 billion.

Counting IBM, we now have large ownership interests in four exceptional companies: 13.0% of

American Express, 8.8% of Coca-Cola, 5.5% of IBM and 7.6% of Wells Fargo. (We also, of course,

have many smaller, but important, positions.)

We view these holdings as partnership interests in wonderful businesses, not as marketable securities to

be bought or sold based on their near-term prospects. Our share of their earnings, however, are far from

fully reflected in our earnings; only the dividends we receive from these businesses show up in our

financial reports. Over time, though, the undistributed earnings of these companies that are attributable

to our ownership are of huge importance to us. That’s because they will be used in a variety of ways to

increase future earnings and dividends of the investee. They may also be devoted to stock repurchases,

which will increase our share of the company’s future earnings.

Had we owned our present positions throughout last year, our dividends from the “Big Four” would

have been $862 million. That’s all that would have been reported in Berkshire’s income statement. Our

share of this quartet’s earnings, however, would have been far greater: $3.3 billion. Charlie and I

believe that the $2.4 billion that goes unreported on our books creates at least that amount of value for

Berkshire as it fuels earnings gains in future years. We expect the combined earnings of the four – and

their dividends as well – to increase in 2012 and, for that matter, almost every year for a long time to

come. A decade from now, our current holdings of the four companies might well account for earnings

of $7 billion, of which $2 billion in dividends would come to us.

I’ve run out of good news. Here are some developments that hurt us during 2011:

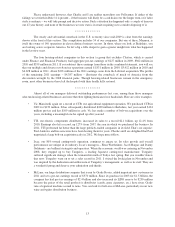

• A few years back, I spent about $2 billion buying several bond issues of Energy Future Holdings, an

electric utility operation serving portions of Texas. That was a mistake – a big mistake. In large measure,

the company’s prospects were tied to the price of natural gas, which tanked shortly after our purchase and

remains depressed. Though we have annually received interest payments of about $102 million since our

purchase, the company’s ability to pay will soon be exhausted unless gas prices rise substantially. We

wrote down our investment by $1 billion in 2010 and by an additional $390 million last year.

At yearend, we carried the bonds at their market value of $878 million. If gas prices remain at present

levels, we will likely face a further loss, perhaps in an amount that will virtually wipe out our current

carrying value. Conversely, a substantial increase in gas prices might allow us to recoup some, or even

all, of our write-down. However things turn out, I totally miscalculated the gain/loss probabilities when

I purchased the bonds. In tennis parlance, this was a major unforced error by your chairman.

4