Berkshire Hathaway 2010 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

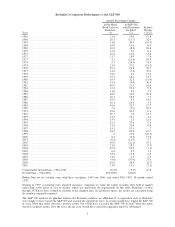

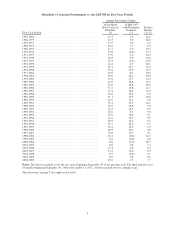

Please find page 9 of the 2010 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.For the forty years, our compounded annual gain in pre-tax, non-insurance earnings per share is 21.0%.

During the same period, Berkshire’s stock price increased at a rate of 22.1% annually. Over time, you can expect

our stock price to move in rough tandem with Berkshire’s investments and earnings. Market price and intrinsic

value often follow very different paths – sometimes for extended periods – but eventually they meet.

There is a third, more subjective, element to an intrinsic value calculation that can be either positive or

negative: the efficacy with which retained earnings will be deployed in the future. We, as well as many other

businesses, are likely to retain earnings over the next decade that will equal, or even exceed, the capital we presently

employ. Some companies will turn these retained dollars into fifty-cent pieces, others into two-dollar bills.

This “what-will-they-do-with-the-money” factor must always be evaluated along with the

“what-do-we-have-now” calculation in order for us, or anybody, to arrive at a sensible estimate of a company’s

intrinsic value. That’s because an outside investor stands by helplessly as management reinvests his share of the

company’s earnings. If a CEO can be expected to do this job well, the reinvestment prospects add to the

company’s current value; if the CEO’s talents or motives are suspect, today’s value must be discounted. The

difference in outcome can be huge. A dollar of then-value in the hands of Sears Roebuck’s or Montgomery

Ward’s CEOs in the late 1960s had a far different destiny than did a dollar entrusted to Sam Walton.

************

Charlie and I hope that the per-share earnings of our non-insurance businesses continue to increase at a

decent rate. But the job gets tougher as the numbers get larger. We will need both good performance from our

current businesses and more major acquisitions. We’re prepared. Our elephant gun has been reloaded, and my

trigger finger is itchy.

Partially offsetting our anchor of size are several important advantages we have. First, we possess a

cadre of truly skilled managers who have an unusual commitment to their own operations and to Berkshire.

Many of our CEOs are independently wealthy and work only because they love what they do. They are

volunteers, not mercenaries. Because no one can offer them a job they would enjoy more, they can’t be lured

away.

At Berkshire, managers can focus on running their businesses: They are not subjected to meetings at

headquarters nor financing worries nor Wall Street harassment. They simply get a letter from me every two years

(it’s reproduced on pages 104-105) and call me when they wish. And their wishes do differ: There are managers

to whom I have not talked in the last year, while there is one with whom I talk almost daily. Our trust is in people

rather than process. A “hire well, manage little” code suits both them and me.

Berkshire’s CEOs come in many forms. Some have MBAs; others never finished college. Some use

budgets and are by-the-book types; others operate by the seat of their pants. Our team resembles a baseball squad

composed of all-stars having vastly different batting styles. Changes in our line-up are seldom required.

Our second advantage relates to the allocation of the money our businesses earn. After meeting the

needs of those businesses, we have very substantial sums left over. Most companies limit themselves to

reinvesting funds within the industry in which they have been operating. That often restricts them, however, to a

“universe” for capital allocation that is both tiny and quite inferior to what is available in the wider world.

Competition for the few opportunities that are available tends to become fierce. The seller has the upper hand, as

a girl might if she were the only female at a party attended by many boys. That lopsided situation would be great

for the girl, but terrible for the boys.

At Berkshire we face no institutional restraints when we deploy capital. Charlie and I are limited only

by our ability to understand the likely future of a possible acquisition. If we clear that hurdle – and frequently we

can’t – we are then able to compare any one opportunity against a host of others.

7