Berkshire Hathaway 2010 Annual Report Download - page 24

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 24 of the 2010 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Academics’ current practice of teaching Black-Scholes as revealed truth needs re-examination. For that

matter, so does the academic’s inclination to dwell on the valuation of options. You can be highly successful as

an investor without having the slightest ability to value an option. What students should be learning is how to

value a business. That’s what investing is all about.

Life and Debt

The fundamental principle of auto racing is that to finish first, you must first finish. That dictum is

equally applicable to business and guides our every action at Berkshire.

Unquestionably, some people have become very rich through the use of borrowed money. However,

that’s also been a way to get very poor. When leverage works, it magnifies your gains. Your spouse thinks you’re

clever, and your neighbors get envious. But leverage is addictive. Once having profited from its wonders, very

few people retreat to more conservative practices. And as we all learned in third grade – and some relearned in

2008 – any series of positive numbers, however impressive the numbers may be, evaporates when multiplied by a

single zero. History tells us that leverage all too often produces zeroes, even when it is employed by very smart

people.

Leverage, of course, can be lethal to businesses as well. Companies with large debts often assume that

these obligations can be refinanced as they mature. That assumption is usually valid. Occasionally, though, either

because of company-specific problems or a worldwide shortage of credit, maturities must actually be met by

payment. For that, only cash will do the job.

Borrowers then learn that credit is like oxygen. When either is abundant, its presence goes unnoticed.

When either is missing, that’s all that is noticed. Even a short absence of credit can bring a company to its knees.

In September 2008, in fact, its overnight disappearance in many sectors of the economy came dangerously close

to bringing our entire country to its knees.

Charlie and I have no interest in any activity that could pose the slightest threat to Berkshire’s well-

being. (With our having a combined age of 167, starting over is not on our bucket list.) We are forever conscious

of the fact that you, our partners, have entrusted us with what in many cases is a major portion of your savings. In

addition, important philanthropy is dependent on our prudence. Finally, many disabled victims of accidents

caused by our insureds are counting on us to deliver sums payable decades from now. It would be irresponsible

for us to risk what all these constituencies need just to pursue a few points of extra return.

A little personal history may partially explain our extreme aversion to financial adventurism. I didn’t

meet Charlie until he was 35, though he grew up within 100 yards of where I have lived for 52 years and also

attended the same inner-city public high school in Omaha from which my father, wife, children and two

grandchildren graduated. Charlie and I did, however, both work as young boys at my grandfather’s grocery store,

though our periods of employment were separated by about five years. My grandfather’s name was Ernest, and

perhaps no man was more aptly named. No one worked for Ernest, even as a stock boy, without being shaped by

the experience.

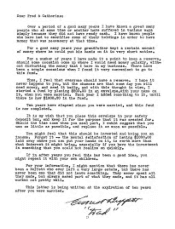

On the facing page you can read a letter sent in 1939 by Ernest to his youngest son, my Uncle Fred.

Similar letters went to his other four children. I still have the letter sent to my Aunt Alice, which I found – along

with $1,000 of cash – when, as executor of her estate, I opened her safe deposit box in 1970.

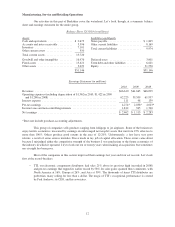

Ernest never went to business school – he never in fact finished high school – but he understood the

importance of liquidity as a condition for assured survival. At Berkshire, we have taken his $1,000 solution a bit

further and have pledged that we will hold at least $10 billion of cash, excluding that held at our regulated utility

and railroad businesses. Because of that commitment, we customarily keep at least $20 billion on hand so that we

can both withstand unprecedented insurance losses (our largest to date having been about $3 billion from Katrina,

the insurance industry’s most expensive catastrophe) and quickly seize acquisition or investment opportunities,

even during times of financial turmoil.

22