Berkshire Hathaway 2008 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 2008 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.MidAmerican has maintained this extraordinary price stability while making Iowa number one among

all states in the percentage of its generation capacity that comes from wind. Since our purchase, MidAmerican’s

wind-based facilities have grown from zero to almost 20% of total capacity.

Similarly, when we purchased PacifiCorp in 2006, we moved aggressively to expand wind generation.

Wind capacity was then 33 megawatts. It’s now 794, with more coming. (Arriving at PacifiCorp, we found

“wind” of a different sort: The company had 98 committees that met frequently. Now there are 28. Meanwhile,

we generate and deliver considerably more electricity, doing so with 2% fewer employees.)

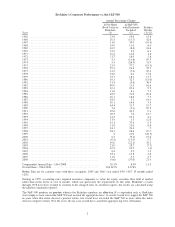

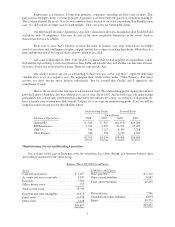

In 2008 alone, MidAmerican spent $1.8 billion on wind generation at our two operations, and today the

company is number one in the nation among regulated utilities in ownership of wind capacity. By the way,

compare that $1.8 billion to the $1.1 billion of pre-tax earnings of PacifiCorp (shown in the table as “Western”)

and Iowa. In our utility business, we spend all we earn, and then some, in order to fulfill the needs of our service

areas. Indeed, MidAmerican has not paid a dividend since Berkshire bought into the company in early 2000. Its

earnings have instead been reinvested to develop the utility systems our customers require and deserve. In

exchange, we have been allowed to earn a fair return on the huge sums we have invested. It’s a great partnership

for all concerned.

************

Our long-avowed goal is to be the “buyer of choice” for businesses – particularly those built and owned

by families. The way to achieve this goal is to deserve it. That means we must keep our promises; avoid

leveraging up acquired businesses; grant unusual autonomy to our managers; and hold the purchased companies

through thick and thin (though we prefer thick and thicker).

Our record matches our rhetoric. Most buyers competing against us, however, follow a different path.

For them, acquisitions are “merchandise.” Before the ink dries on their purchase contracts, these operators are

contemplating “exit strategies.” We have a decided advantage, therefore, when we encounter sellers who truly

care about the future of their businesses.

Some years back our competitors were known as “leveraged-buyout operators.” But LBO became a

bad name. So in Orwellian fashion, the buyout firms decided to change their moniker. What they did not change,

though, were the essential ingredients of their previous operations, including their cherished fee structures and

love of leverage.

Their new label became “private equity,” a name that turns the facts upside-down: A purchase of a

business by these firms almost invariably results in dramatic reductions in the equity portion of the acquiree’s

capital structure compared to that previously existing. A number of these acquirees, purchased only two to three

years ago, are now in mortal danger because of the debt piled on them by their private-equity buyers. Much of

the bank debt is selling below 70¢ on the dollar, and the public debt has taken a far greater beating. The private-

equity firms, it should be noted, are not rushing in to inject the equity their wards now desperately need. Instead,

they’re keeping their remaining funds very private.

In the regulated utility field there are no large family-owned businesses. Here, Berkshire hopes to be

the “buyer of choice” of regulators. It is they, rather than selling shareholders, who judge the fitness of

purchasers when transactions are proposed.

There is no hiding your history when you stand before these regulators. They can – and do – call their

counterparts in other states where you operate and ask how you have behaved in respect to all aspects of the

business, including a willingness to commit adequate equity capital.

7