Berkshire Hathaway 2012 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 2012 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

Insurance

Let’s look first at insurance, Berkshire’s core operation and the engine that has propelled our expansion

over the years.

Property-casualty (“P/C”) insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such

as those arising from certain workers’ compensation accidents, payments can stretch over decades. This collect-

now, pay-later model leaves us holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others.

Meanwhile, we get to invest this float for Berkshire’s benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go,

the amount of float we hold remains quite stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business

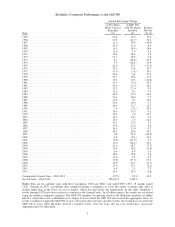

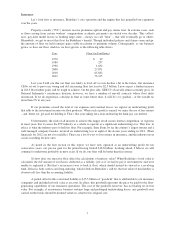

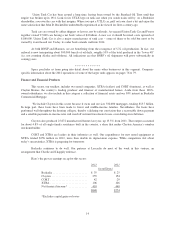

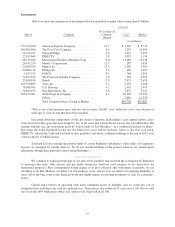

grows, so does our float. And how we have grown, as the following table shows:

Year Float (in $ millions)

1970 $ 39

1980 237

1990 1,632

2000 27,871

2010 65,832

2012 73,125

Last year I told you that our float was likely to level off or even decline a bit in the future. Our insurance

CEOs set out to prove me wrong and did, increasing float last year by $2.5 billion. I now expect a further increase

in 2013. But further gains will be tough to achieve. On the plus side, GEICO’s float will almost certainly grow. In

National Indemnity’s reinsurance division, however, we have a number of run-off contracts whose float drifts

downward. If we do experience a decline in float at some future time, it will be very gradual – at the outside no

more than 2% in any year.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit

that adds to the investment income our float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money

– and, better yet, get paid for holding it. That’s like your taking out a loan and having the bank pay you interest.

Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous

in most years that it causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in

effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. For example, State Farm, by far the country’s largest insurer and a

well-managed company besides, incurred an underwriting loss in eight of the eleven years ending in 2011. (Their

financials for 2012 are not yet available.) There are a lot of ways to lose money in insurance, and the industry never

ceases searching for new ones.

As noted in the first section of this report, we have now operated at an underwriting profit for ten

consecutive years, our pre-tax gain for the period having totaled $18.6 billion. Looking ahead, I believe we will

continue to underwrite profitably in most years. If we do, our float will be better than free money.

So how does our attractive float affect the calculations of intrinsic value? When Berkshire’s book value is

calculated, the full amount of our float is deducted as a liability, just as if we had to pay it out tomorrow and were

unable to replenish it. But that’s an incorrect way to look at float, which should instead be viewed as a revolving

fund. If float is both costless and long-enduring, which I believe Berkshire’s will be, the true value of this liability is

dramatically less than the accounting liability.

A partial offset to this overstated liability is $15.5 billion of “goodwill” that is attributable to our insurance

companies and included in book value as an asset. In effect, this goodwill represents the price we paid for the float-

generating capabilities of our insurance operations. The cost of the goodwill, however, has no bearing on its true

value. For example, if an insurance business sustains large and prolonged underwriting losses, any goodwill asset

carried on the books should be deemed valueless, whatever its original cost.

7