Berkshire Hathaway 2012 Annual Report Download - page 10

Download and view the complete annual report

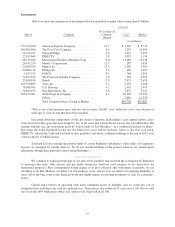

Please find page 10 of the 2012 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Fortunately, that’s not the case at Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our insurance

goodwill – what we would happily pay to purchase an insurance operation producing float of similar quality –tobe

far in excess of its historic carrying value. The value of our float is one reason – a huge reason – why we believe

Berkshire’s intrinsic business value substantially exceeds its book value.

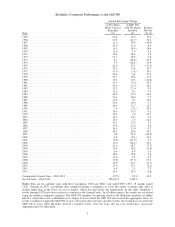

Let me emphasize once again that cost-free float is not an outcome to be expected for the P/C industry as a

whole: There is very little “Berkshire-quality” float existing in the insurance world. In 37 of the 45 years ending in

2011, the industry’s premiums have been inadequate to cover claims plus expenses. Consequently, the industry’s

overall return on tangible equity has for many decades fallen far short of the average return realized by American

industry, a sorry performance almost certain to continue.

A further unpleasant reality adds to the industry’s dim prospects: Insurance earnings are now benefitting

from “legacy” bond portfolios that deliver much higher yields than will be available when funds are reinvested

during the next few years – and perhaps for many years beyond that. Today’s bond portfolios are, in effect, wasting

assets. Earnings of insurers will be hurt in a significant way as bonds mature and are rolled over.

************

Berkshire’s outstanding economics exist only because we have some terrific managers running some

extraordinary insurance operations. Let me tell you about the major units.

First by float size is the Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group, run by Ajit Jain. Ajit insures risks that no

one else has the desire or the capital to take on. His operation combines capacity, speed, decisiveness and, most

important, brains in a manner unique in the insurance business. Yet he never exposes Berkshire to risks that are

inappropriate in relation to our resources. Indeed, we are far more conservative in avoiding risk than most large

insurers. For example, if the insurance industry should experience a $250 billion loss from some mega-catastrophe

– a loss about triple anything it has ever experienced – Berkshire as a whole would likely record a significant profit

for the year because it has so many streams of earnings. All other major insurers and reinsurers would meanwhile

be far in the red, with some facing insolvency.

From a standing start in 1985, Ajit has created an insurance business with float of $35 billion and a

significant cumulative underwriting profit, a feat that no other insurance CEO has come close to matching. He has

thus added a great many billions of dollars to the value of Berkshire. If you meet Ajit at the annual meeting, bow

deeply.

************

We have another reinsurance powerhouse in General Re, managed by Tad Montross.

At bottom, a sound insurance operation needs to adhere to four disciplines. It must (1) understand all

exposures that might cause a policy to incur losses; (2) conservatively assess the likelihood of any exposure actually

causing a loss and the probable cost if it does; (3) set a premium that, on average, will deliver a profit after both

prospective loss costs and operating expenses are covered; and (4) be willing to walk away if the appropriate

premium can’t be obtained.

Many insurers pass the first three tests and flunk the fourth. They simply can’t turn their back on business

that is being eagerly written by their competitors. That old line, “The other guy is doing it, so we must as well,”

spells trouble in any business, but none more so than insurance.

8