Berkshire Hathaway 2004 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

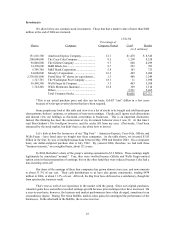

Please find page 9 of the 2004 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. Finally, there is a fear factor at work, in that a shrinking business usually leads to layoffs. To

avoid pink slips, employees will rationalize inadequate pricing, telling themselves that poorly-priced

business must be tolerated in order to keep the organization intact and the distribution system happy. If this

course isn’ t followed, these employees will argue, the company will not participate in the recovery that

they invariably feel is just around the corner.

To combat employees’ natural tendency to save their own skins, we have always promised

NICO’ s workforce that no one will be fired because of declining volume, however severe the contraction.

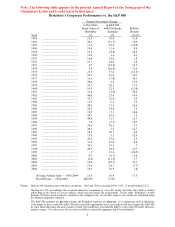

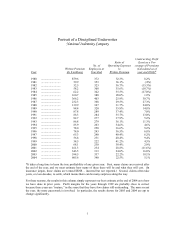

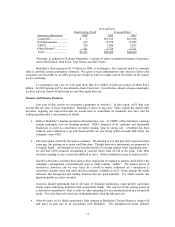

(This is not Donald Trump’ s sort of place.) NICO is not labor-intensive, and, as the table suggests, can live

with excess overhead. It can’ t live, however, with underpriced business and the breakdown in underwriting

discipline that accompanies it. An insurance organization that doesn’ t care deeply about underwriting at a

profit this year is unlikely to care next year either.

Naturally, a business that follows a no-layoff policy must be especially careful to avoid

overstaffing when times are good. Thirty years ago Tom Murphy, then CEO of Cap Cities, drove this point

home to me with a hypothetical tale about an employee who asked his boss for permission to hire an

assistant. The employee assumed that adding $20,000 to the annual payroll would be inconsequential. But

his boss told him the proposal should be evaluated as a $3 million decision, given that an additional person

would probably cost at least that amount over his lifetime, factoring in raises, benefits and other expenses

(more people, more toilet paper). And unless the company fell on very hard times, the employee added

would be unlikely to be dismissed, however marginal his contribution to the business.

It takes real fortitude – embedded deep within a company’ s culture – to operate as NICO does.

Anyone examining the table can scan the years from 1986 to 1999 quickly. But living day after day with

dwindling volume – while competitors are boasting of growth and reaping Wall Street’ s applause – is an

experience few managers can tolerate. NICO, however, has had four CEOs since its formation in 1940 and

none have bent. (It should be noted that only one of the four graduated from college. Our experience tells

us that extraordinary business ability is largely innate.)

The current managerial star – make that superstar – at NICO is Don Wurster (yes, he’ s “the

graduate”), who has been running things since 1989. His slugging percentage is right up there with Barry

Bonds’ because, like Barry, Don will accept a walk rather than swing at a bad pitch. Don has now amassed

$950 million of float at NICO that over time is almost certain to be proved the negative-cost kind. Because

insurance prices are falling, Don’ s volume will soon decline very significantly and, as it does, Charlie and I

will applaud him ever more loudly.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Another way to prosper in a commodity-type business is to be the low-cost operator. Among auto

insurers operating on a broad scale, GEICO holds that cherished title. For NICO, as we have seen, an ebb-

and-flow business model makes sense. But a company holding a low-cost advantage must pursue an

unrelenting foot-to-the-floor strategy. And that’ s just what we do at GEICO.

A century ago, when autos first appeared, the property-casualty industry operated as a cartel. The

major companies, most of which were based in the Northeast, established “bureau” rates and that was it.

No one cut prices to attract business. Instead, insurers competed for strong, well-regarded agents, a focus

that produced high commissions for agents and high prices for consumers.

In 1922, State Farm was formed by George Mecherle, a farmer from Merna, Illinois, who aimed to

take advantage of the pricing umbrella maintained by the high-cost giants of the industry. State Farm

employed a “captive” agency force, a system keeping its acquisition costs lower than those incurred by the

bureau insurers (whose “independent” agents successfully played off one company against another). With

its low-cost structure, State Farm eventually captured about 25% of the personal lines (auto and

homeowners) business, far outdistancing its once-mighty competitors. Allstate, formed in 1931, put a

similar distribution system into place and soon became the runner-up in personal lines to State Farm.

Capitalism had worked its magic, and these low-cost operations looked unstoppable.

8