Berkshire Hathaway 2004 Annual Report Download - page 20

Download and view the complete annual report

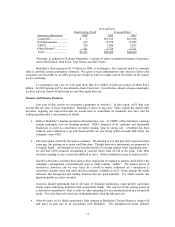

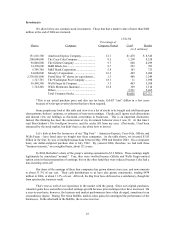

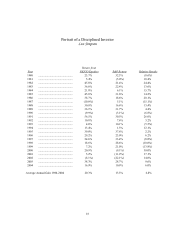

Please find page 20 of the 2004 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. Even then, it is typically not I who make the buying decisions. Lou Simpson manages about $2½

billion of equities that are held by GEICO, and it is his transactions that Berkshire is usually reporting.

Customarily his purchases are in the $200-$300 million range and are in companies that are smaller than

the ones I focus on. Take a look at the facing page to see why Lou is a cinch to be inducted into the

investment Hall of Fame.

You may be surprised to learn that Lou does not necessarily inform me about what he is doing.

When Charlie and I assign responsibility, we truly hand over the baton – and we give it to Lou just as we

do to our operating managers. Therefore, I typically learn of Lou’ s transactions about ten days after the

end of each month. Sometimes, it should be added, I silently disagree with his decisions. But he’ s usually right.

Foreign Currencies

Berkshire owned about $21.4 billion of foreign exchange contracts at yearend, spread among 12

currencies. As I mentioned last year, holdings of this kind are a decided change for us. Before March

2002, neither Berkshire nor I had ever traded in currencies. But the evidence grows that our trade policies

will put unremitting pressure on the dollar for many years to come – so since 2002 we’ ve heeded that

warning in setting our investment course. (As W.C. Fields once said when asked for a handout: “Sorry,

son, all my money’ s tied up in currency.”)

Be clear on one point: In no way does our thinking about currencies rest on doubts about America.

We live in an extraordinarily rich country, the product of a system that values market economics, the rule

of law and equality of opportunity. Our economy is far and away the strongest in the world and will

continue to be. We are lucky to live here.

But as I argued in a November 10, 2003 article in Fortune, (available at berkshirehathaway.com),

our country’ s trade practices are weighing down the dollar. The decline in its value has already been

substantial, but is nevertheless likely to continue. Without policy changes, currency markets could even

become disorderly and generate spillover effects, both political and financial. No one knows whether these

problems will materialize. But such a scenario is a far-from-remote possibility that policymakers should be

considering now. Their bent, however, is to lean toward not-so-benign neglect: A 318-page Congressional

study of the consequences of unremitting trade deficits was published in November 2000 and has been

gathering dust ever since. The study was ordered after the deficit hit a then-alarming $263 billion in 1999;

by last year it had risen to $618 billion.

Charlie and I, it should be emphasized, believe that true trade – that is, the exchange of goods and

services with other countries – is enormously beneficial for both us and them. Last year we had $1.15

trillion of such honest-to-God trade and the more of this, the better. But, as noted, our country also

purchased an additional $618 billion in goods and services from the rest of the world that was

unreciprocated. That is a staggering figure and one that has important consequences.

The balancing item to this one-way pseudo-trade — in economics there is always an offset — is a

transfer of wealth from the U.S. to the rest of the world. The transfer may materialize in the form of IOUs

our private or governmental institutions give to foreigners, or by way of their assuming ownership of our

assets, such as stocks and real estate. In either case, Americans end up owning a reduced portion of our

country while non-Americans own a greater part. This force-feeding of American wealth to the rest of the

world is now proceeding at the rate of $1.8 billion daily, an increase of 20% since I wrote you last year.

Consequently, other countries and their citizens now own a net of about $3 trillion of the U.S. A decade

ago their net ownership was negligible.

The mention of trillions numbs most brains. A further source of confusion is that the current

account deficit (the sum of three items, the most important by far being the trade deficit) and our national

budget deficit are often lumped as “twins.” They are anything but. They have different causes and

different consequences.

19