Berkshire Hathaway 2004 Annual Report Download - page 23

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 23 of the 2004 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.At our sessions, I tell the newcomers the story of the Tennessee group and its spotting of Clayton

Homes. I do this in the spirit of the farmer who enters his hen house with an ostrich egg and

admonishes the flock: “I don’ t like to complain, girls, but this is just a small sample of what the

competition is doing.” To date, our new scouts have not brought us deals. But their mission in

life has been made clear to them.

• You should be aware of an accounting rule that mildly distorts our financial statements in a pain-

today, gain-tomorrow manner. Berkshire purchases life insurance policies from individuals and

corporations who would otherwise surrender them for cash. As the new holder of the policies, we

pay any premiums that become due and ultimately – when the original holder dies – collect the

face value of the policies.

The original policyholder is usually in good health when we purchase the policy. Still, the price

we pay for it is always well above its cash surrender value (“CSV”). Sometimes the original

policyholder has borrowed against the CSV to make premium payments. In that case, the

remaining CSV will be tiny and our purchase price will be a large multiple of what the original

policyholder would have received, had he cashed out by surrendering it.

Under accounting rules, we must immediately charge as a realized capital loss the excess over

CSV that we pay upon purchasing the policy. We also must make additional charges each year for

the amount by which the premium we pay to keep the policy in force exceeds the increase in CSV.

But obviously, we don’ t think these bookkeeping charges represent economic losses. If we did,

we wouldn’ t buy the policies.

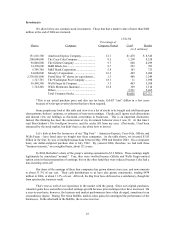

During 2004, we recorded net “losses” from the purchase of policies (and from the premium

payments required to maintain them) totaling $207 million, which was charged against realized

investment gains in our earnings statement (included in “other” in the table on page 17). When

the proceeds from these policies are received in the future, we will record as realized investment

gain the excess over the then-CSV.

• Two post-bubble governance reforms have been particularly useful at Berkshire, and I fault myself

for not putting them in place many years ago. The first involves regular meetings of directors

without the CEO present. I’ ve sat on 19 boards, and on many occasions this process would have

led to dubious plans being examined more thoroughly. In a few cases, CEO changes that were

needed would also have been made more promptly. There is no downside to this process, and

there are many possible benefits.

The second reform concerns the “whistleblower line,” an arrangement through which employees

can send information to me and the board’ s audit committee without fear of reprisal. Berkshire’ s

extreme decentralization makes this system particularly valuable both to me and the committee.

(In a sprawling “city” of 180,000 – Berkshire’ s current employee count – not every sparrow that

falls will be noticed at headquarters.) Most of the complaints we have received are of “the guy

next to me has bad breath” variety, but on occasion I have learned of important problems at our

subsidiaries that I otherwise would have missed. The issues raised are usually not of a type

discoverable by audit, but relate instead to personnel and business practices. Berkshire would be

more valuable today if I had put in a whistleblower line decades ago.

• Charlie and I love the idea of shareholders thinking and behaving like owners. Sometimes that

requires them to be pro-active. And in this arena large institutional owners should lead the way.

So far, however, the moves made by institutions have been less than awe-inspiring. Usually,

they’ ve focused on minutiae and ignored the three questions that truly count. First, does the

company have the right CEO? Second, is he/she overreaching in terms of compensation? Third,

are proposed acquisitions more likely to create or destroy per-share value?

22