Berkshire Hathaway 2003 Annual Report Download - page 7

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 7 of the 2003 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.6

more expensive and restrictive terms than was previously the case. This tightening was particularly serious

for Clayton, whose earnings significantly depended on securitizations.

Today, the manufactured housing industry remains awash in problems. Delinquencies continue

high, repossessed units still abound and the number of retailers has been halved. A different business

model is required, one that eliminates the ability of the retailer and salesman to pocket substantial money

up front by making sales financed by loans that are destined to default. Such transactions cause hardship to

both buyer and lender and lead to a flood of repossessions that then undercut the sale of new units. Under a

proper model – one requiring significant down payments and shorter-term loans – the industry will likely

remain much smaller than it was in the 90s. But it will deliver to home buyers an asset in which they will

have equity, rather than disappointment, upon resale.

In the “full circle” department, Clayton has agreed to buy the assets of Oakwood. When the

transaction closes, Clayton’ s manufacturing capacity, geographical reach and sales outlets will be

substantially increased. As a byproduct, the debt of Oakwood that we own, which we bought at a deep

discount, will probably return a small profit to us.

And the students? In October, we had a surprise “graduation” ceremony in Knoxville for the 40

who sparked my interest in Clayton. I donned a mortarboard and presented each student with both a PhD

(for phenomenal, hard-working dealmaker) from Berkshire and a B share. Al got an A share. If you meet

some of the new Tennessee shareholders at our annual meeting, give them your thanks. And ask them if

they’ ve read any good books lately.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

In early spring, Byron Trott, a Managing Director of Goldman Sachs, told me that Wal-Mart

wished to sell its McLane subsidiary. McLane distributes groceries and nonfood items to convenience

stores, drug stores, wholesale clubs, mass merchandisers, quick service restaurants, theaters and others. It’ s

a good business, but one not in the mainstream of Wal-Mart’ s future. It’ s made to order, however, for us.

McLane has sales of about $23 billion, but operates on paper-thin margins – about 1% pre-tax –

and will swell Berkshire’ s sales figures far more than our income. In the past, some retailers had shunned

McLane because it was owned by their major competitor. Grady Rosier, McLane’ s superb CEO, has

already landed some of these accounts – he was in full stride the day the deal closed – and more will come.

For several years, I have given my vote to Wal-Mart in the balloting for Fortune Magazine’ s

“Most Admired” list. Our McLane transaction reinforced my opinion. To make the McLane deal, I had a

single meeting of about two hours with Tom Schoewe, Wal-Mart’ s CFO, and we then shook hands. (He

did, however, first call Bentonville). Twenty-nine days later Wal-Mart had its money. We did no “due

diligence.” We knew everything would be exactly as Wal-Mart said it would be – and it was.

I should add that Byron has now been instrumental in three Berkshire acquisitions. He

understands Berkshire far better than any investment banker with whom we have talked and – it hurts me to

say this – earns his fee. I’ m looking forward to deal number four (as, I am sure, is he).

Taxes

On May 20, 2003, The Washington Post ran an op-ed piece by me that was critical of the Bush tax

proposals. Thirteen days later, Pamela Olson, Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy at the U.S. Treasury,

delivered a speech about the new tax legislation saying, “That means a certain midwestern oracle, who, it

must be noted, has played the tax code like a fiddle, is still safe retaining all his earnings.” I think she was

talking about me.

Alas, my “fiddle playing” will not get me to Carnegie Hall – or even to a high school recital.

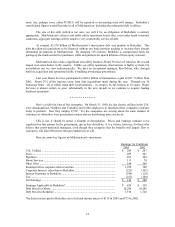

Berkshire, on your behalf and mine, will send the Treasury $3.3 billion for tax on its 2003 income, a sum

equaling 2½% of the total income tax paid by all U.S. corporations in fiscal 2003. (In contrast, Berkshire’ s

market valuation is about 1% of the value of all American corporations.) Our payment will almost