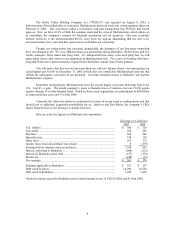

Berkshire Hathaway 2005 Annual Report Download - page 19

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 19 of the 2005 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.How to Minimize Investment Returns

It’ s been an easy matter for Berkshire and other owners of American equities to prosper over the

years. Between December 31, 1899 and December 31, 1999, to give a really long-term example, the Dow

rose from 66 to 11,497. (Guess what annual growth rate is required to produce this result; the surprising

answer is at the end of this section.) This huge rise came about for a simple reason: Over the century

American businesses did extraordinarily well and investors rode the wave of their prosperity. Businesses

continue to do well. But now shareholders, through a series of self-inflicted wounds, are in a major way

cutting the returns they will realize from their investments.

The explanation of how this is happening begins with a fundamental truth: With unimportant

exceptions, such as bankruptcies in which some of a company’ s losses are borne by creditors, the most that

owners in aggregate can earn between now and Judgment Day is what their businesses in aggregate earn.

True, by buying and selling that is clever or lucky, investor A may take more than his share of the pie at the

expense of investor B. And, yes, all investors feel richer when stocks soar. But an owner can exit only by

having someone take his place. If one investor sells high, another must buy high. For owners as a whole,

there is simply no magic – no shower of money from outer space – that will enable them to extract wealth

from their companies beyond that created by the companies themselves.

Indeed, owners must earn less than their businesses earn because of “frictional” costs. And that’ s

my point: These costs are now being incurred in amounts that will cause shareholders to earn far less than

they historically have.

To understand how this toll has ballooned, imagine for a moment that all American corporations

are, and always will be, owned by a single family. We’ ll call them the Gotrocks. After paying taxes on

dividends, this family – generation after generation – becomes richer by the aggregate amount earned by its

companies. Today that amount is about $700 billion annually. Naturally, the family spends some of these

dollars. But the portion it saves steadily compounds for its benefit. In the Gotrocks household everyone

grows wealthier at the same pace, and all is harmonious.

But let’ s now assume that a few fast-talking Helpers approach the family and persuade each of its

members to try to outsmart his relatives by buying certain of their holdings and selling them certain others.

The Helpers – for a fee, of course – obligingly agree to handle these transactions. The Gotrocks still own

all of corporate America; the trades just rearrange who owns what. So the family’ s annual gain in wealth

diminishes, equaling the earnings of American business minus commissions paid. The more that family

members trade, the smaller their share of the pie and the larger the slice received by the Helpers. This fact

is not lost upon these broker-Helpers: Activity is their friend and, in a wide variety of ways, they urge it on.

After a while, most of the family members realize that they are not doing so well at this new “beat-

my-brother” game. Enter another set of Helpers. These newcomers explain to each member of the

Gotrocks clan that by himself he’ ll never outsmart the rest of the family. The suggested cure: “Hire a

manager – yes, us – and get the job done professionally.” These manager-Helpers continue to use the

broker-Helpers to execute trades; the managers may even increase their activity so as to permit the brokers

to prosper still more. Overall, a bigger slice of the pie now goes to the two classes of Helpers.

The family’ s disappointment grows. Each of its members is now employing professionals. Yet

overall, the group’ s finances have taken a turn for the worse. The solution? More help, of course.

It arrives in the form of financial planners and institutional consultants, who weigh in to advise the

Gotrocks on selecting manager-Helpers. The befuddled family welcomes this assistance. By now its

members know they can pick neither the right stocks nor the right stock-pickers. Why, one might ask,

should they expect success in picking the right consultant? But this question does not occur to the

Gotrocks, and the consultant-Helpers certainly don’ t suggest it to them.

18