Berkshire Hathaway 2005 Annual Report Download - page 17

Download and view the complete annual report

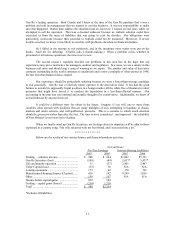

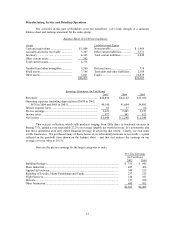

Please find page 17 of the 2005 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. Upon taking office at Gillette, Jim quickly instilled fiscal discipline, tightened operations and

energized marketing, moves that dramatically increased the intrinsic value of the company. Gillette’ s

merger with P&G then expanded the potential of both companies. For his accomplishments, Jim was paid

very well – but he earned every penny. (This is no academic evaluation: As a 9.7% owner of Gillette,

Berkshire in effect paid that proportion of his compensation.) Indeed, it’ s difficult to overpay the truly

extraordinary CEO of a giant enterprise. But this species is rare.

Too often, executive compensation in the U.S. is ridiculously out of line with performance. That

won’ t change, moreover, because the deck is stacked against investors when it comes to the CEO’ s pay.

The upshot is that a mediocre-or-worse CEO – aided by his handpicked VP of human relations and a

consultant from the ever-accommodating firm of Ratchet, Ratchet and Bingo – all too often receives gobs

of money from an ill-designed compensation arrangement.

Take, for instance, ten year, fixed-price options (and who wouldn’ t?). If Fred Futile, CEO of

Stagnant, Inc., receives a bundle of these – let’ s say enough to give him an option on 1% of the company –

his self-interest is clear: He should skip dividends entirely and instead use all of the company’ s earnings to

repurchase stock.

Let’ s assume that under Fred’ s leadership Stagnant lives up to its name. In each of the ten years

after the option grant, it earns $1 billion on $10 billion of net worth, which initially comes to $10 per share

on the 100 million shares then outstanding. Fred eschews dividends and regularly uses all earnings to

repurchase shares. If the stock constantly sells at ten times earnings per share, it will have appreciated

158% by the end of the option period. That’ s because repurchases would reduce the number of shares to

38.7 million by that time, and earnings per share would thereby increase to $25.80. Simply by withholding

earnings from owners, Fred gets very rich, making a cool $158 million, despite the business itself

improving not at all. Astonishingly, Fred could have made more than $100 million if Stagnant’ s earnings

had declined by 20% during the ten-year period.

Fred can also get a splendid result for himself by paying no dividends and deploying the earnings

he withholds from shareholders into a variety of disappointing projects and acquisitions. Even if these

initiatives deliver a paltry 5% return, Fred will still make a bundle. Specifically – with Stagnant’ s p/e ratio

remaining unchanged at ten – Fred’ s option will deliver him $63 million. Meanwhile, his shareholders will

wonder what happened to the “alignment of interests” that was supposed to occur when Fred was issued

options.

A “normal” dividend policy, of course – one-third of earnings paid out, for example – produces

less extreme results but still can provide lush rewards for managers who achieve nothing.

CEOs understand this math and know that every dime paid out in dividends reduces the value of

all outstanding options. I’ ve never, however, seen this manager-owner conflict referenced in proxy

materials that request approval of a fixed-priced option plan. Though CEOs invariably preach internally

that capital comes at a cost, they somehow forget to tell shareholders that fixed-price options give them

capital that is free.

It doesn’ t have to be this way: It’ s child’ s play for a board to design options that give effect to the

automatic build-up in value that occurs when earnings are retained. But – surprise, surprise – options of

that kind are almost never issued. Indeed, the very thought of options with strike prices that are adjusted

for retained earnings seems foreign to compensation “experts,” who are nevertheless encyclopedic about

every management-friendly plan that exists. (“Whose bread I eat, his song I sing.”)

Getting fired can produce a particularly bountiful payday for a CEO. Indeed, he can “earn” more

in that single day, while cleaning out his desk, than an American worker earns in a lifetime of cleaning

toilets. Forget the old maxim about nothing succeeding like success: Today, in the executive suite, the all-

too-prevalent rule is that nothing succeeds like failure.

16