Berkshire Hathaway 2005 Annual Report Download - page 11

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 11 of the 2005 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Finance and Financial Products

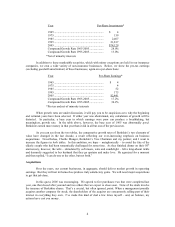

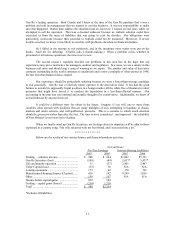

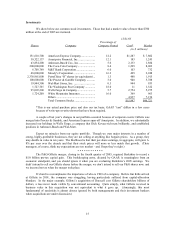

The star of our finance sector is Clayton Homes, masterfully run by Kevin Clayton. He does not

owe his brilliant record to a rising tide: The manufactured-housing business has been disappointing since

Berkshire purchased Clayton in 2003. Industry sales have stagnated at 40-year lows, and the recent uptick

from Katrina-related demand will almost certainly be short-lived. In recent years, many industry

participants have suffered losses, and only Clayton has earned significant money.

In this brutal environment Clayton has bought a large amount of manufactured-housing loans from

major banks that found them unprofitable and difficult to service. Clayton’ s operating expertise and

Berkshire’ s financial resources have made this an excellent business for us and one in which we are

preeminent. We presently service $17 billion of loans, compared to $5.4 billon at the time of our purchase.

Moreover, Clayton now owns $9.6 billion of its servicing portfolio, a position built up almost entirely since

Berkshire entered the picture.

To finance this portfolio, Clayton borrows money from Berkshire, which in turn borrows the same

amount publicly. For the use of its credit, Berkshire charges Clayton a one percentage-point markup on its

borrowing cost. In 2005, the cost to Clayton for this arrangement was $83 million. That amount is

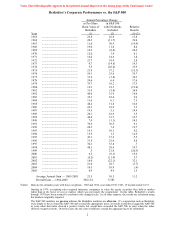

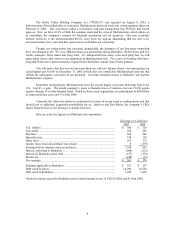

included in “Other” income in the table on the facing page, and Clayton’ s earnings of $416 million are after

deducting this payment.

On the manufacturing side, Clayton has also been active. To its original base of twenty plants, it

first added twelve more in 2004 by way of the bankruptcy purchase of Oakwood, which just a few years

earlier was one of the largest companies in the business. Then in 2005 Clayton purchased Karsten, a four-

plant operation that greatly strengthens Clayton’ s position on the West Coast.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Long ago, Mark Twain said: “A man who tries to carry a cat home by its tail will learn a lesson

that can be learned in no other way.” If Twain were around now, he might try winding up a derivatives

business. After a few days, he would opt for cats.

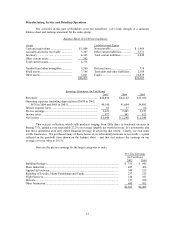

We lost $104 million pre-tax last year in our continuing attempt to exit Gen Re’ s derivative

operation. Our aggregate losses since we began this endeavor total $404 million.

Originally we had 23,218 contracts outstanding. By the start of 2005 we were down to 2,890.

You might expect that our losses would have been stemmed by this point, but the blood has kept flowing.

Reducing our inventory to 741 contracts last year cost us the $104 million mentioned above.

Remember that the rationale for establishing this unit in 1990 was Gen Re’ s wish to meet the

needs of insurance clients. Yet one of the contracts we liquidated in 2005 had a term of 100 years! It’ s

difficult to imagine what “need” such a contract could fulfill except, perhaps, the need of a compensation-

conscious trader to have a long-dated contract on his books. Long contracts, or alternatively those with

multiple variables, are the most difficult to mark to market (the standard procedure used in accounting for

derivatives) and provide the most opportunity for “imagination” when traders are estimating their value.

Small wonder that traders promote them.

A business in which huge amounts of compensation flow from assumed numbers is obviously

fraught with danger. When two traders execute a transaction that has several, sometimes esoteric, variables

and a far-off settlement date, their respective firms must subsequently value these contracts whenever they

calculate their earnings. A given contract may be valued at one price by Firm A and at another by Firm B.

You can bet that the valuation differences – and I’ m personally familiar with several that were huge – tend

to be tilted in a direction favoring higher earnings at each firm. It’ s a strange world in which two parties

can carry out a paper transaction that each can promptly report as profitable.

I dwell on our experience in derivatives each year for two reasons. One is personal and

unpleasant. The hard fact is that I have cost you a lot of money by not moving immediately to close down

10