Berkshire Hathaway 2009 Annual Report Download - page 6

Download and view the complete annual report

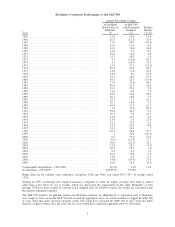

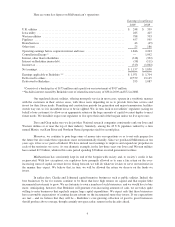

Please find page 6 of the 2009 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.We should note that had we instead chosen market prices as our yardstick, Berkshire’s results would

look better, showing a gain since the start of fiscal 1965 of 22% compounded annually. Surprisingly, this modest

difference in annual compounding rate leads to an 801,516% market-value gain for the entire 45-year period

compared to the book-value gain of 434,057% (shown on page 2). Our market gain is better because in 1965

Berkshire shares sold at an appropriate discount to the book value of its underearning textile assets, whereas

today Berkshire shares regularly sell at a premium to the accounting values of its first-class businesses.

Summed up, the table on page 2 conveys three messages, two positive and one hugely negative. First,

we have never had any five-year period beginning with 1965-69 and ending with 2005-09 – and there have been

41 of these – during which our gain in book value did not exceed the S&P’s gain. Second, though we have lagged

the S&P in some years that were positive for the market, we have consistently done better than the S&P in the

eleven years during which it delivered negative results. In other words, our defense has been better than our

offense, and that’s likely to continue.

The big minus is that our performance advantage has shrunk dramatically as our size has grown, an

unpleasant trend that is certain to continue. To be sure, Berkshire has many outstanding businesses and a cadre of

truly great managers, operating within an unusual corporate culture that lets them maximize their talents. Charlie

and I believe these factors will continue to produce better-than-average results over time. But huge sums forge

their own anchor and our future advantage, if any, will be a small fraction of our historical edge.

What We Don’t Do

Long ago, Charlie laid out his strongest ambition: “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll

never go there.” That bit of wisdom was inspired by Jacobi, the great Prussian mathematician, who counseled

“Invert, always invert” as an aid to solving difficult problems. (I can report as well that this inversion approach

works on a less lofty level: Sing a country song in reverse, and you will quickly recover your car, house and

wife.)

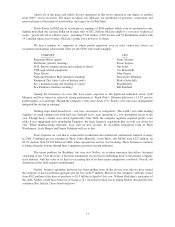

Here are a few examples of how we apply Charlie’s thinking at Berkshire:

• Charlie and I avoid businesses whose futures we can’t evaluate, no matter how exciting their

products may be. In the past, it required no brilliance for people to foresee the fabulous growth

that awaited such industries as autos (in 1910), aircraft (in 1930) and television sets (in 1950). But

the future then also included competitive dynamics that would decimate almost all of the

companies entering those industries. Even the survivors tended to come away bleeding.

Just because Charlie and I can clearly see dramatic growth ahead for an industry does not mean

we can judge what its profit margins and returns on capital will be as a host of competitors battle

for supremacy. At Berkshire we will stick with businesses whose profit picture for decades to

come seems reasonably predictable. Even then, we will make plenty of mistakes.

• We will never become dependent on the kindness of strangers. Too-big-to-fail is not a fallback

position at Berkshire. Instead, we will always arrange our affairs so that any requirements for cash

we may conceivably have will be dwarfed by our own liquidity. Moreover, that liquidity will be

constantly refreshed by a gusher of earnings from our many and diverse businesses.

When the financial system went into cardiac arrest in September 2008, Berkshire was a supplier

of liquidity and capital to the system, not a supplicant. At the very peak of the crisis, we poured

$15.5 billion into a business world that could otherwise look only to the federal government for

help. Of that, $9 billion went to bolster capital at three highly-regarded and previously-secure

American businesses that needed – without delay – our tangible vote of confidence. The remaining

$6.5 billion satisfied our commitment to help fund the purchase of Wrigley, a deal that was

completed without pause while, elsewhere, panic reigned.

4