Berkshire Hathaway 2009 Annual Report Download - page 19

Download and view the complete annual report

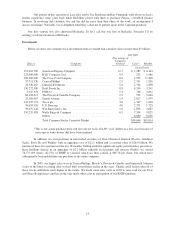

Please find page 19 of the 2009 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.If an acquirer’s stock is overvalued, it’s a different story: Using it as a currency works to the acquirer’s

advantage. That’s why bubbles in various areas of the stock market have invariably led to serial issuances of

stock by sly promoters. Going by the market value of their stock, they can afford to overpay because they are, in

effect, using counterfeit money. Periodically, many air-for-assets acquisitions have taken place, the late 1960s

having been a particularly obscene period for such chicanery. Indeed, certain large companies were built in this

way. (No one involved, of course, ever publicly acknowledges the reality of what is going on, though there is

plenty of private snickering.)

In our BNSF acquisition, the selling shareholders quite properly evaluated our offer at $100 per share.

The cost to us, however, was somewhat higher since 40% of the $100 was delivered in our shares, which Charlie

and I believed to be worth more than their market value. Fortunately, we had long owned a substantial amount of

BNSF stock that we purchased in the market for cash. All told, therefore, only about 30% of our cost overall was

paid with Berkshire shares.

In the end, Charlie and I decided that the disadvantage of paying 30% of the price through stock was

offset by the opportunity the acquisition gave us to deploy $22 billion of cash in a business we understood and

liked for the long term. It has the additional virtue of being run by Matt Rose, whom we trust and admire. We

also like the prospect of investing additional billions over the years at reasonable rates of return. But the final

decision was a close one. If we had needed to use more stock to make the acquisition, it would in fact have made

no sense. We would have then been giving up more than we were getting.

************

I have been in dozens of board meetings in which acquisitions have been deliberated, often with the

directors being instructed by high-priced investment bankers (are there any other kind?). Invariably, the bankers

give the board a detailed assessment of the value of the company being purchased, with emphasis on why it is

worth far more than its market price. In more than fifty years of board memberships, however, never have I heard

the investment bankers (or management!) discuss the true value of what is being given. When a deal involved the

issuance of the acquirer’s stock, they simply used market value to measure the cost. They did this even though

they would have argued that the acquirer’s stock price was woefully inadequate – absolutely no indicator of its

real value – had a takeover bid for the acquirer instead been the subject up for discussion.

When stock is the currency being contemplated in an acquisition and when directors are hearing from

an advisor, it appears to me that there is only one way to get a rational and balanced discussion. Directors should

hire a second advisor to make the case against the proposed acquisition, with its fee contingent on the deal not

going through. Absent this drastic remedy, our recommendation in respect to the use of advisors remains: “Don’t

ask the barber whether you need a haircut.”

************

I can’t resist telling you a true story from long ago. We owned stock in a large well-run bank that for

decades had been statutorily prevented from acquisitions. Eventually, the law was changed and our bank

immediately began looking for possible purchases. Its managers – fine people and able bankers – not

unexpectedly began to behave like teenage boys who had just discovered girls.

They soon focused on a much smaller bank, also well-run and having similar financial characteristics

in such areas as return on equity, interest margin, loan quality, etc. Our bank sold at a modest price (that’s why

we had bought into it), hovering near book value and possessing a very low price/earnings ratio. Alongside,

though, the small-bank owner was being wooed by other large banks in the state and was holding out for a price

close to three times book value. Moreover, he wanted stock, not cash.

Naturally, our fellows caved in and agreed to this value-destroying deal. “We need to show that we are

in the hunt. Besides, it’s only a small deal,” they said, as if only major harm to shareholders would have been a

legitimate reason for holding back. Charlie’s reaction at the time: “Are we supposed to applaud because the dog

that fouls our lawn is a Chihuahua rather than a Saint Bernard?”

17