Berkshire Hathaway 2006 Annual Report Download - page 23

Download and view the complete annual report

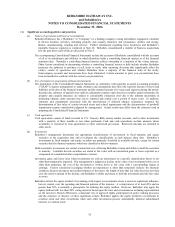

Please find page 23 of the 2006 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.The inexorable math of this grotesque arrangement is certain to make the Gotrocks family poorer

over time than it would have been had it never heard of these “hyper-helpers.” Even so, the 2-and-20

action spreads. Its effects bring to mind the old adage: When someone with experience proposes a deal to

someone with money, too often the fellow with money ends up with the experience, and the fellow with

experience ends up with the money.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Let me end this section by telling you about one of the good guys of Wall Street, my long-time

friend Walter Schloss, who last year turned 90. From 1956 to 2002, Walter managed a remarkably

successful investment partnership, from which he took not a dime unless his investors made money. My

admiration for Walter, it should be noted, is not based on hindsight. A full fifty years ago, Walter was my

sole recommendation to a St. Louis family who wanted an honest and able investment manager.

Walter did not go to business school, or for that matter, college. His office contained one file

cabinet in 1956; the number mushroomed to four by 2002. Walter worked without a secretary, clerk or

bookkeeper, his only associate being his son, Edwin, a graduate of the North Carolina School of the Arts.

Walter and Edwin never came within a mile of inside information. Indeed, they used “outside” information

only sparingly, generally selecting securities by certain simple statistical methods Walter learned while

working for Ben Graham. When Walter and Edwin were asked in 1989 by Outstanding Investors Digest,

“How would you summarize your approach?” Edwin replied, “We try to buy stocks cheap.” So much for

Modern Portfolio Theory, technical analysis, macroeconomic thoughts and complex algorithms.

Following a strategy that involved no real risk – defined as permanent loss of capital – Walter

produced results over his 47 partnership years that dramatically surpassed those of the S&P 500. It’ s

particularly noteworthy that he built this record by investing in about 1,000 securities, mostly of a

lackluster type. A few big winners did not account for his success. It’ s safe to say that had millions of

investment managers made trades by a) drawing stock names from a hat; b) purchasing these stocks in

comparable amounts when Walter made a purchase; and then c) selling when Walter sold his pick, the

luckiest of them would not have come close to equaling his record. There is simply no possibility that what

Walter achieved over 47 years was due to chance.

I first publicly discussed Walter’ s remarkable record in 1984. At that time “efficient market

theory” (EMT) was the centerpiece of investment instruction at most major business schools. This theory,

as then most commonly taught, held that the price of any stock at any moment is not demonstrably

mispriced, which means that no investor can be expected to overperform the stock market averages using

only publicly-available information (though some will do so by luck). When I talked about Walter 23 years

ago, his record forcefully contradicted this dogma.

And what did members of the academic community do when they were exposed to this new and

important evidence? Unfortunately, they reacted in all-too-human fashion: Rather than opening their

minds, they closed their eyes. To my knowledge no business school teaching EMT made any attempt to

study Walter’ s performance and what it meant for the school’ s cherished theory.

Instead, the faculties of the schools went merrily on their way presenting EMT as having the

certainty of scripture. Typically, a finance instructor who had the nerve to question EMT had about as

much chance of major promotion as Galileo had of being named Pope.

Tens of thousands of students were therefore sent out into life believing that on every day the price

of every stock was “right” (or, more accurately, not demonstrably wrong) and that attempts to evaluate

businesses – that is, stocks – were useless. Walter meanwhile went on overperforming, his job made easier

by the misguided instructions that had been given to those young minds. After all, if you are in the

shipping business, it’ s helpful to have all of your potential competitors be taught that the earth is flat.

Maybe it was a good thing for his investors that Walter didn’ t go to college.

22