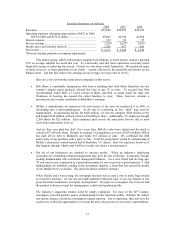

Berkshire Hathaway 2006 Annual Report Download - page 22

Download and view the complete annual report

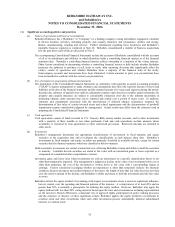

Please find page 22 of the 2006 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.Those people favoring perpetual foundations argue that in the future there will most certainly be

large and important societal problems that philanthropy will need to address. I agree. But there will then

also be many super-rich individuals and families whose wealth will exceed that of today’ s Americans and

to whom philanthropic organizations can make their case for funding. These funders can then judge

firsthand which operations have both the vitality and the focus to best address the major societal problems

that then exist. In this way, a market test of ideas and effectiveness can be applied. Some organizations

will deserve major support while others will have outlived their usefulness. Even if the people above

ground make their decisions imperfectly, they should be able to allocate funds more rationally than a

decedent six feet under will have ordained decades earlier. Wills, of course, can always be rewritten, but

it’ s very unlikely that my thinking will change in a material way.

A few shareholders have expressed concern that sales of Berkshire by the foundations receiving

shares will depress the stock. These fears are unwarranted. The annual trading volume of many stocks

exceeds 100% of the outstanding shares, but nevertheless these stocks usually sell at prices approximating

their intrinsic value. Berkshire also tends to sell at an appropriate price, but with annual volume that is only

15% of shares outstanding. At most, sales by the foundations receiving my shares will add three

percentage points to annual trading volume, which will still leave Berkshire with a turnover ratio that is the

lowest around.

Overall, Berkshire’ s business performance will determine the price of our stock, and most of the

time it will sell in a zone of reasonableness. It’ s important that the foundations receive appropriate prices

as they periodically sell Berkshire shares, but it’ s also important that incoming shareholders don’ t overpay.

(See economic principle 14 on page 77.) By both our policies and shareholder communications, Charlie

and I will do our best to ensure that Berkshire sells at neither a large discount nor large premium to intrinsic

value.

The existence of foundation ownership will in no way influence our board’ s decisions about

dividends, repurchases, or the issuance of shares. We will follow exactly the same rule that has guided us

in the past: What action will be likely to deliver the best result for shareholders over time?

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

In last year’ s report I allegorically described the Gotrocks family – a clan that owned all of

America’ s businesses and that counterproductively attempted to increase its investment returns by paying

ever-greater commissions and fees to “helpers.” Sad to say, the “family” continued its self-destructive

ways in 2006.

In part the family persists in this folly because it harbors unrealistic expectations about obtainable

returns. Sometimes these delusions are self-serving. For example, private pension plans can temporarily

overstate their earnings, and public pension plans can defer the need for increased taxes, by using

investment assumptions that are likely to be out of reach. Actuaries and auditors go along with these

tactics, and it can be decades before the chickens come home to roost (at which point the CEO or public

official who misled the world is apt to be gone).

Meanwhile, Wall Street’ s Pied Pipers of Performance will have encouraged the futile hopes of the

family. The hapless Gotrocks will be assured that they all can achieve above-average investment

performance – but only by paying ever-higher fees. Call this promise the adult version of Lake Woebegon.

In 2006, promises and fees hit new highs. A flood of money went from institutional investors to

the 2-and-20 crowd. For those innocent of this arrangement, let me explain: It’ s a lopsided system whereby

2% of your principal is paid each year to the manager even if he accomplishes nothing – or, for that matter,

loses you a bundle – and, additionally, 20% of your profit is paid to him if he succeeds, even if his success

is due simply to a rising tide. For example, a manager who achieves a gross return of 10% in a year will

keep 3.6 percentage points – two points off the top plus 20% of the residual 8 points – leaving only 6.4

percentage points for his investors. On a $3 billion fund, this 6.4% net “performance” will deliver the

manager a cool $108 million. He will receive this bonanza even though an index fund might have returned

15% to investors in the same period and charged them only a token fee.

21