Berkshire Hathaway 2007 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

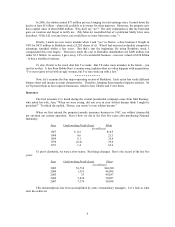

Please find page 9 of the 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. Nevertheless, this business requires a significant reinvestment of earnings if it is to grow. When

we purchased FlightSafety in 1996, its pre-tax operating earnings were $111 million, and its net investment

in fixed assets was $570 million. Since our purchase, depreciation charges have totaled $923 million. But

capital expenditures have totaled $1.635 billion, most of that for simulators to match the new airplane

models that are constantly being introduced. (A simulator can cost us more than $12 million, and we have

273 of them.) Our fixed assets, after depreciation, now amount to $1.079 billion. Pre-tax operating

earnings in 2007 were $270 million, a gain of $159 million since 1996. That gain gave us a good, but far

from See’ s-like, return on our incremental investment of $509 million.

Consequently, if measured only by economic returns, FlightSafety is an excellent but not

extraordinary business. Its put-up-more-to-earn-more experience is that faced by most corporations. For

example, our large investment in regulated utilities falls squarely in this category. We will earn

considerably more money in this business ten years from now, but we will invest many billions to make it.

Now let’ s move to the gruesome. The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires

significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a

durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a

farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by

shooting Orville down.

The airline industry’ s demand for capital ever since that first flight has been insatiable. Investors

have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it.

And I, to my shame, participated in this foolishness when I had Berkshire buy U.S. Air preferred stock in

1989. As the ink was drying on our check, the company went into a tailspin, and before long our preferred

dividend was no longer being paid. But we then got very lucky. In one of the recurrent, but always

misguided, bursts of optimism for airlines, we were actually able to sell our shares in 1998 for a hefty gain.

In the decade following our sale, the company went bankrupt. Twice.

To sum up, think of three types of “savings accounts.” The great one pays an extraordinarily high

interest rate that will rise as the years pass. The good one pays an attractive rate of interest that will be

earned also on deposits that are added. Finally, the gruesome account both pays an inadequate interest rate

and requires you to keep adding money at those disappointing returns.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

And now it’ s confession time. It should be noted that no consultant, board of directors or

investment banker pushed me into the mistakes I will describe. In tennis parlance, they were all unforced

errors.

To begin with, I almost blew the See’ s purchase. The seller was asking $30 million, and I was

adamant about not going above $25 million. Fortunately, he caved. Otherwise I would have balked, and

that $1.35 billion would have gone to somebody else.

About the time of the See’ s purchase, Tom Murphy, then running Capital Cities Broadcasting,

called and offered me the Dallas-Fort Worth NBC station for $35 million. The station came with the Fort

Worth paper that Capital Cities was buying, and under the “cross-ownership” rules Murph had to divest it.

I knew that TV stations were See’ s-like businesses that required virtually no capital investment and had

excellent prospects for growth. They were simple to run and showered cash on their owners.

Moreover, Murph, then as now, was a close friend, a man I admired as an extraordinary manager

and outstanding human being. He knew the television business forward and backward and would not have

called me unless he felt a purchase was certain to work. In effect Murph whispered “buy” into my ear. But

I didn’ t listen.

8