Berkshire Hathaway 2007 Annual Report Download - page 8

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 8 of the 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report. Long-term competitive advantage in a stable industry is what we seek in a business. If that comes

with rapid organic growth, great. But even without organic growth, such a business is rewarding. We will

simply take the lush earnings of the business and use them to buy similar businesses elsewhere. There’ s no

rule that you have to invest money where you’ ve earned it. Indeed, it’ s often a mistake to do so: Truly

great businesses, earning huge returns on tangible assets, can’t for any extended period reinvest a large

portion of their earnings internally at high rates of return.

Let’ s look at the prototype of a dream business, our own See’ s Candy. The boxed-chocolates

industry in which it operates is unexciting: Per-capita consumption in the U.S. is extremely low and doesn’ t

grow. Many once-important brands have disappeared, and only three companies have earned more than

token profits over the last forty years. Indeed, I believe that See’ s, though it obtains the bulk of its revenues

from only a few states, accounts for nearly half of the entire industry’ s earnings.

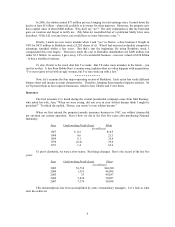

At See’ s, annual sales were 16 million pounds of candy when Blue Chip Stamps purchased the

company in 1972. (Charlie and I controlled Blue Chip at the time and later merged it into Berkshire.) Last

year See’ s sold 31 million pounds, a growth rate of only 2% annually. Yet its durable competitive

advantage, built by the See’ s family over a 50-year period, and strengthened subsequently by Chuck

Huggins and Brad Kinstler, has produced extraordinary results for Berkshire.

We bought See’ s for $25 million when its sales were $30 million and pre-tax earnings were less

than $5 million. The capital then required to conduct the business was $8 million. (Modest seasonal debt

was also needed for a few months each year.) Consequently, the company was earning 60% pre-tax on

invested capital. Two factors helped to minimize the funds required for operations. First, the product was

sold for cash, and that eliminated accounts receivable. Second, the production and distribution cycle was

short, which minimized inventories.

Last year See’ s sales were $383 million, and pre-tax profits were $82 million. The capital now

required to run the business is $40 million. This means we have had to reinvest only $32 million since

1972 to handle the modest physical growth – and somewhat immodest financial growth – of the business.

In the meantime pre-tax earnings have totaled $1.35 billion. All of that, except for the $32 million, has

been sent to Berkshire (or, in the early years, to Blue Chip). After paying corporate taxes on the profits, we

have used the rest to buy other attractive businesses. Just as Adam and Eve kick-started an activity that led

to six billion humans, See’ s has given birth to multiple new streams of cash for us. (The biblical command

to “be fruitful and multiply” is one we take seriously at Berkshire.)

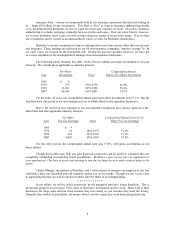

There aren’ t many See’ s in Corporate America. Typically, companies that increase their earnings

from $5 million to $82 million require, say, $400 million or so of capital investment to finance their

growth. That’ s because growing businesses have both working capital needs that increase in proportion to

sales growth and significant requirements for fixed asset investments.

A company that needs large increases in capital to engender its growth may well prove to be a

satisfactory investment. There is, to follow through on our example, nothing shabby about earning $82

million pre-tax on $400 million of net tangible assets. But that equation for the owner is vastly different

from the See’ s situation. It’ s far better to have an ever-increasing stream of earnings with virtually no

major capital requirements. Ask Microsoft or Google.

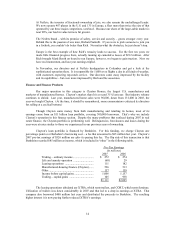

One example of good, but far from sensational, business economics is our own FlightSafety. This

company delivers benefits to its customers that are the equal of those delivered by any business that I know

of. It also possesses a durable competitive advantage: Going to any other flight-training provider than the

best is like taking the low bid on a surgical procedure.

7