Berkshire Hathaway 2000 Annual Report Download - page 7

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 7 of the 2000 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.6

Acme, the larger of the two operations, produces more than one billion bricks per year at its 22

plants, about 11.7% of the industry’s national output. The brick business, however, is necessarily

regional, and in its territory Acme enjoys unquestioned leadership. When Texans are asked to

name a brand of brick, 75% respond Acme, compared to 16% for the runner-up. (Before our

purchase, I couldn’t have named a brand of brick. Could you have?) This brand recognition is

not only due to Acme’s product quality, but also reflects many decades of extraordinary

community service by both the company and John Justin.

I can’t resist pointing out that Berkshire — whose top mana gement has long been mired in the

19th century — is now one of the very few authentic “clicks-and-bricks” businesses around. We

went into 2000 with GEICO doing significant business on the Internet, and then we added Acme.

You can bet this move by Berkshire is making them sweat in Silicon Valley.

•In June, Bob Shaw, CEO of Shaw Industries, the world’s largest carpet manufacturer, came to

see me with his partner, Julian Saul, and the CEO of a second company with which Shaw was

mulling a merger. The potential partner, however, faced huge asbestos liabilities from past

activities, and any deal depended on these being eliminated through insurance.

The executives visiting me wanted Berkshire to provide a policy that would pay all future

asbestos costs. I explained that though we could write an exceptionally large policy — far larger

than any other insurer would ever think of offering — we would never issue a policy that lacked

a cap.

Bob and Julian decided that if we didn’t want to bet the ranch on the exte nt of the acquiree’s

liability, neither did they. So their deal died. But my interest in Shaw was sparked, and a few

months later Charlie and I met with Bob to work out a purchase by Berkshire. A key feature of

the deal was that both Bob and Julian were to continue owning at least 5% of Shaw. This leaves

us associated with the best in the business as shown by Bob and Julian’s record: Each built a

large, successful carpet business before joining forces in 1998.

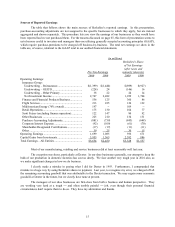

Shaw has annual sales of about $4 billion, and we own 87.3% of the company. Leaving aside our

insurance operation, Shaw is by far our largest business. Now, if people walk all over us, we

won’t mind.

•In July, Bob Mundheim, a director of Benjamin Moore Paint, called to ask if Berkshire might

be interested in acquiring it. I knew Bob from Salomon, where he was general counsel during

some difficult times, and held him in very high regard. So my answer was “Tell me more.”

In late August, Charlie and I met with Richard Roob and Yvan Dupuy, past and present CEOs of

Benjamin Moore. We liked them; we liked the business; and we made a $1 billion cash offer on

the spot. In October, their board approved the transaction, and we completed it in December.

Benjamin Moore has been making paint for 117 years and has thousands of independent dealers

that are a vital asset to its business. Make sure you specify our product for your next paint job.

•Finally, in late December, we agreed to buy Johns Manville Corp. for about $1.8 billion. This

company’s incredible odyssey over the last few decades too multifaceted to be chronicled here

was shaped by its long history as a manufacturer of asbestos products. The much-publicized

health problems that affected many people exposed to asbestos led to JM’s declaring bankruptcy

in 1982.

Subsequently, the bankruptcy court established a trust for victims, the major asset of which was a

controlling interest in JM. The trust, which sensibly wanted to diversify its assets, agreed last

June to sell the business to an LBO buyer. In the end, though, the LBO group was unable to

obtain financing.