Berkshire Hathaway 2000 Annual Report Download - page 66

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 66 of the 2000 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.65

PURCHASE-ACCOUNTING ADJUSTMENTS

Next: spinach time. I know that a discussion of accounting technicalities turns off many readers, so let me assure

you that a full and happy life can still be yours if you decide to skip this section.

Our 1996 acquisition of GEICO, however, means that purchase-accounting adjustments of about $40 million are

charged against our annual earnings as recorded under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Our General Re

acquisition will produce an annual charge many times this number, but we don’t have final figures at this time. So the

magnitude of these charges makes them a subject of importance to Berkshire. In our annual reports, therefore, we will

sometimes talk of earnings that we will describe as "before purchase-accounting adjustments." The discussion that follows

will tell you why we think earnings of that description have far more economic meaning than the earnings produced by

GAAP.

When Berkshire buys a business for a premium over the GAAP net worth of the acquiree — as will usually be the

case, since most companies we'd want to buy don't come at a discount — that premium has to be entered on the asset side of

our balance sheet. There are loads of rules about just how a company should record the premium. But to simplify this

discussion, we will focus on "Goodwill," the asset item to which almost all of Berkshire's acquisition premiums have been

allocated. For example, when we acquired in 1996 the half of GEICO we didn't previously own, we recorded goodwill of

about $1.6 billion.

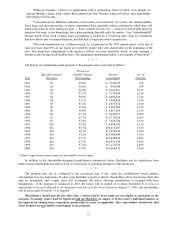

GAAP requires goodwill to be amortized — that is, written off — over a period no longer than 40 years. Therefore,

to extinguish our $1.6 billion in GEICO goodwill, we will take annual charges of about $40 million until 2036. This

amount is not deductible for tax purposes, so it reduces both our pre-tax and after-tax earnings by $40 million.

In an accounting sense, consequently, our GEICO goodwill will disappear gradually in even-sized bites. But the

one thing I can guarantee you is that the economic goodwill we have purchased at GEICO will not decline in the same

measured way. In fact, my best guess is that the economic goodwill assignable to GEICO has dramatically increased since

our purchase and will likely continue to increase — quite probably in a very substantial way.

I made a similar statement in our 1983 Annual Report about the goodwill attributed to See's Candy, when I used

that company as an example in a discussion of goodwill accounting. At that time, our balance sheet carried about $36

million of See's goodwill. We have since been charging about $1 million against earnings every year in order to amortize

the asset, and the See's goodwill on our balance sheet is now down to about $21 million. In other words, from an accounting

standpoint, See's is now presented as having lost a good deal of goodwill since 1983.

The economic facts could not be more different. In 1983, See's earned about $27 million pre-tax on $11 million of

net operating assets; in 1997 it earned $59 million on $5 million of net operating assets. Clearly See's economic goodwill

has increased dramatically during the interval rather than decreased. Just as clearly, See's is worth many hundreds of

millions of dollars more than its stated value on our books.

We could, of course, be wrong, but we expect that GEICO's gradual loss of accounting value will continue to be

paired with major increases in its economic value. Certainly that has been the pattern at most of our subsidiaries, not just

See's. That is why we regularly present our operating earnings in a way that allows you to ignore all purchase-accounting

adjustments.

Before leaving this subject, we should issue an important warning: Investors are often led astray by CEOs and

Wall Street analysts who equate depreciation charges with the amortization charges we have just discussed. In no way are

the two the same: With rare exceptions, depreciation is an economic cost every bit as real as wages, materials, or taxes.

Certainly that is true at Berkshire and at virtually all the other businesses we have studied. Furthermore, we do not think so-

called EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is a meaningful measure of performance.

Managements that dismiss the importance of depreciation — and emphasize "cash flow" or EBITDA — are apt to make

faulty decisions, and you should keep that in mind as you make your own investment decisions.

THE MANAGING OF BERKSHIRE

I think it's appropriate that I conclude with a discussion of Berkshire's management, today and in the future. As

our first owner-related principle tells you, Charlie and I are the managing partners of Berkshire. But we subcontract all of

the heavy lifting in this business to the managers of our subsidiaries. In fact, we delegate almost to the point of abdication:

Though Berkshire has about 45,000 employees, only 12 of these are at headquarters.