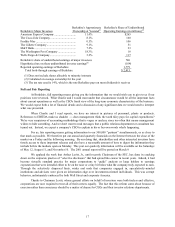

Berkshire Hathaway 2000 Annual Report Download - page 12

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 12 of the 2000 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.11

The financial consequences of these boners are regularly dumped into massive restructuring charges or

write-offs that are casually waved off as “nonrecurring.” Managements just love these. Indeed, in recent years it

has seemed that no earnings statement is complete without them. The origins of these charges, though, are never

explored. When it comes to corporate blunders, CEOs invoke the concept of the Virgin Birth.

To get back to our examination of GEICO: There are at least four factors that could account for the

increased costs we experienced in obtaining new business last year, and all probably contributed in some manner.

First, in our advertising we have pushed “frequency” very hard, and we probably overstepped in certain

media. We’ve always known that increasing the number of messages through any medium would eventually

produce diminishing returns. The third ad in an hour on a given cable channel is simply not going to be as effective

as the first.

Second, we may have already picked much of the low-hanging fruit. Clearly, the willingness to do

business with a direct marketer of insurance varies widely among individuals: Indeed, some percentage of

Americans particularly older ones are reluctant to make direct purchases of any kind. Over the years,

however, this reluctance will ebb. A new generation with new habits will find the savings from direct purchase of

their auto insurance too compelling to ignore.

Another factor that surely decreased the conversion of inquiries into sales was stricter underwriting by

GEICO. Both the frequency and severity of losses increased during the year, and rates in certain areas became

inadequate, in some cases substantially so. In these instances, we necessarily tightened our underwriting standards.

This tightening, as well as the many rate increases we put in during the year, made our offerings less attractive to

some prospects.

A high percentage of callers, it should be emphasized, can still save money by insuring with us.

Understandably, however, some prospects will switch to save $200 per year but will not switch to save $50.

Therefore, rate increases that bring our prices closer to those of our competitors will hurt our acceptance rate, even

when we continue to offer the best deal.

Finally, the competitive picture changed in at least one important respect: State Farm by far the largest

personal auto insurer, with about 19% of the market — has been very slow to raise prices. Its costs, however, are

clearly increasing right along with those of the rest of the industry. Consequently, State Farm had an underwriting

loss last year from auto insurance (including rebates to policyholders) of 18% of premiums, compared to 4% at

GEICO. Our loss produced a float cost for us of 6.1%, an unsatisfactory result. (Indeed, at GEICO we expect float,

over time, to be free.) But we estimate that State Farm’s float cost in 2000 was about 23%. The willingness of the

largest player in the industry to tolerate such a cost makes the economics difficult for other participants.

That does not take away from the fact that State Farm is one of America’s greatest business stories. I’ve

urged that the company be studied at business schools because it has achieved fabulous success while following a

path that in many ways defies the dogma of those institutions. Studying counter-evidence is a highly useful activity,

though not one always greeted with enthusiasm at citadels of learning.

State Farm was launched in 1922, by a 45-year-old, semi-retired Illinois farmer, to compete with long-

established insurers haughty institutions in New York, Philadelphia and Hartford that possessed

overwhelming advantages in capital, reputation, and distribution. Because State Farm is a mutual company, its

board members and managers could not be owners, and it had no access to capital markets during its years of fast

growth. Similarly, the business never had the stock options or lavish salaries that many people think vital if an

American enterprise is to attract able managers and thrive.

In the end, however, State Farm eclipsed all its competitors. In fact, by 1999 the company had amassed a

tangible net worth exceeding that of all but four American businesses. If you want to read how this happened, get a

copy of The Farmer from Merna.