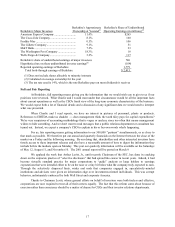

Berkshire Hathaway 2000 Annual Report Download - page 10

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 10 of the 2000 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.9

these on us in a manner that penalizes our current earnings but gives us float we can use for many years to come.

After the loss that we incur in the first year of the policy, there are no further costs attached to this business.

When these policies are properly priced, we welcome the pain-today, gain-tomorrow effects they have. In

1999, $400 million of our underwriting loss (about 27.8% of the total) came from business of this kind and in 2000

the figure was $482 million (34.4% of our loss). We have no way of predicting how much similar business we will

write in the future, but what we do get will typically be in large chunks. Because these transactions can materially

distort our figures, we will tell you about them as they occur.

Other reinsurers have little taste for this insurance. They simply can’t stomach what hu ge underwriting

losses do to their reported results, even though these losses are produced by policies whose overall economics are

certain to be favorable. You should be careful, therefore, in comparing our underwriting results with those of other

insurers.

An even more significant item in our numbers — which, again, you won’t find much of elsewhere —

arises from transactions in which we assume past losses of a company that wants to put its troubles behind it. To

illustrate, the XYZ insurance company might have last year bought a policy obligating us to pay the first $1 billion

of losses and loss adjustment expenses from events that happened in, say, 1995 and earlier years. These contracts

can be very large, though we always require a cap on our exposure. We entered into a number of such transactions

in 2000 and expect to close several more in 2001.

Under GAAP accounting, this “retroactive” insurance neither benefits nor penalizes our current earnings.

Instead, we set up an asset called “deferred charges applicable to assumed reinsurance,” in an amount reflecting

the difference between the premium we receive and the (higher) losses we expect to pay (for which reserves are

immediately established). We then amortize this asset by making annual charges to earnings that create equivalent

underwriting losses. You will find the amount of the loss that we incur from these transactions in both our

quarterly and annual management discussion. By their nature, these losses will continue for many years, often

stretching into decades. As an offset, though, we have the use of float lots of it.

Clearly, float carrying an annual cost of this kind is not as desirable as float we generate from policies that

are expected to produce an underwriting profit (of which we have plenty). Nevertheless, this retroactive insurance

should be decent business for us.

The net of all this is that a) I expect our cost of float to be very attractive in the future but b) rarely to

return to a “no-cost” mode because of the annual charge that retroactive reinsurance will lay on us. Also —

obviously the ultimate benefits that we derive from float will depend not only on its cost but, fully as important,

how effectively we deploy it.

Our retroactive business is almost single-handedly the work of Ajit Jain, whose praises I sing annually. It

is impossible to overstate how valuable Ajit is to Berkshire. Don’t worry about my health; worry about his.

Last year, Ajit brought home a $2.4 billion reinsurance premium, perhaps the largest in history, from a

policy that retroactively covers a major U.K. company. Subsequently, he wrote a large policy protecting the Texas

Rangers from the possibility that Alex Rodriguez will become permanently disabled. As sports fans know, “A-Rod”

was signed for $252 million, a record, and we think that our policy probably also set a record for disability

insurance. We cover many other sports figures as well.

In another example of his versatility, Ajit last fall negotiated a very interesting deal with Grab.com, an

Internet company whose goal was to attract millions of people to its site and there to extract information from them

that would be useful to marketers. To lure these people, Grab.com held out the possibility of a $1 billion prize

(having a $170 million present value) and we insured its payment. A message on the site explained that the

chance of anyone winning the prize was low, and indeed no one won. But the possibility of a win was far from nil.

Writing such a policy, we receive a modest premium, face the possibility of a huge loss, and get good

odds. Very few insurers like that equation. And they’re unable to cure their unhappiness by reinsurance. Because

each policy has unusual and sometimes unique characteristics, insurers can’t lay off the occasional shock loss