Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 8

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 8 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

7

Historically, Berkshire has obtained its float at a very low cost. Indeed, our cost has been less than zero in

about half of the years in which weve operated; that is, weve actually been paid for holding other peoples money.

Over the last few years, however, our cost has been too high, and in 2001 it was terrible.

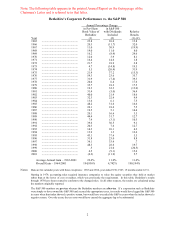

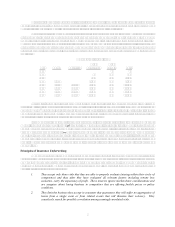

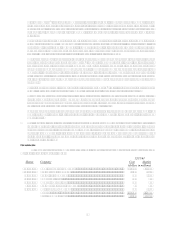

The table that follows shows (at intervals) the float generated by the various segments of Berkshires

insurance operations since we entered the business 35 years ago upon acquiring National Indemnity Company

(whose traditional lines are included in the segment Other Primary). For the table we have calculated our float

which we generate in large amounts relative to our premium volume by adding net loss reserves, loss adjustment

reserves, funds held under reinsurance assumed and unearned premium reserves, and then subtracting insurance-

related receivables, prepaid acquisition costs, prepaid taxes and deferred charges applicable to assumed reinsurance.

(Got that?)

Yearend Float (in $ millions)

Other Other

Year GEICO General Re Reinsurance Primary Total

1967 20 20

1977 40 131 171

1987 701 807 1,508

1997 2,917 4,014 455 7,386

1998 3,125 14,909 4,305 415 22,754

1999 3,444 15,166 6,285 403 25,298

2000 3,943 15,525 7,805 598 27,871

2001 4,251 19,310 11,262 685 35,508

Last year I told you that, barring a mega-catastrophe, our cost of float would probably drop from its 2000

level of 6%. I had in mind natural catastrophes when I said that, but instead we were hit by a man-made catastrophe

on September 11th an event that delivered the insurance industry its largest loss in history. Our float cost therefore

came in at a staggering 12.8%. It was our worst year in float cost since 1984, and a result that to a significant

degree, as I will explain in the next section, we brought upon ourselves.

If no mega-catastrophe occurs, I once again expect the cost of our float to be low in the coming year.

We will indeed need a low cost, as will all insurers. Some years back, float costing, say, 4% was tolerable because

government bonds yielded twice as much, and stocks prospectively offered still loftier returns. Today, fat returns

are nowhere to be found (at least we cant find them) and short-term funds earn less than 2%. Under these

conditions, each of our insurance operations, save one, must deliver an underwriting profit if it is to be judged a

good business. The exception is our retroactive reinsurance operation (a business we explained in last years annual

report), which has desirable economics even though it currently hits us with an annual underwriting loss of about

$425 million.

Principles of Insurance Underwriting

When property/casualty companies are judged by their cost of float, very few stack up as satisfactory

businesses. And interestingly unlike the situation prevailing in many other industries neither size nor brand

name determines an insurers profitability. Indeed, many of the biggest and best-known companies regularly

deliver mediocre results. What counts in this business is underwriting discipline. The winners are those that

unfailingly stick to three key principles:

1. They accept only those risks that they are able to properly evaluate (staying within their circle of

competence) and that, after they have evaluated all relevant factors including remote loss

scenarios, carry the expectancy of profit. These insurers ignore market-share considerations and

are sanguine about losing business to competitors that are offering foolish prices or policy

conditions.

2. They limit the business they accept in a manner that guarantees they will suffer no aggregation of

losses from a single event or from related events that will threaten their solvency. They

ceaselessly search for possible correlation among seemingly-unrelated risks.