Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 65

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 65 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.64

5. Because of our two-pronged approach to business ownership and because of the limitations of

conventional accounting, consolidated reported earnings may reveal relatively little about our true

economic performance. Charlie and I, both as owners and managers, virtually ignore such consolidated

numbers. However, we will also report to you the earnings of each major business we control, numbers we

consider of great importance. These figures, along with other information we will supply about the

individual businesses, should generally aid you in making judgments about them.

To state things simply, we try to give you in the annual report the numbers and other information that

really matter. Charlie and I pay a great deal of attention to how well our businesses are doing, and we also

work to understand the environment in which each business is operating. For example, is one of our

businesses enjoying an industry tailwind or is it facing a headwind? Charlie and I need to know exactly

which situation prevails and to adjust our expectations accordingly. We will also pass along our

conclusions to you.

Over time, practically all of our businesses have exceeded our expectations. But occasionally we have

disappointments, and we will try to be as candid in informing you about those as we are in describing the

happier experiences. When we use unconventional measures to chart our progress — for instance, you will

be reading in our annual reports about insurance "float" — we will try to explain these concepts and why

we regard them as important. In other words, we believe in telling you how we think so that you can

evaluate not only Berkshire's businesses but also assess our approach to management and capital allocation.

6. Accounting consequences do not influence our operating or capital-allocation decisions. When acquisition

costs are similar, we much prefer to purchase $2 of earnings that is not reportable by us under standard

accounting principles than to purchase $1 of earnings that is reportable. This is precisely the choice that

often faces us since entire businesses (whose earnings will be fully reportable) frequently sell for double

the pro-rata price of small portions (whose earnings will be largely unreportable). In aggregate and over

time, we expect the unreported earnings to be fully reflected in our intrinsic business value through capital

gains.

We have found over time that the undistributed earnings of our investees, in aggregate, have been fully as

beneficial to Berkshire as if they had been distributed to us (and therefore had been included in the

earnings we officially report). This pleasant result has occurred because most of our investees are engaged

in truly outstanding businesses that can often employ incremental capital to great advantage, either by

putting it to work in their businesses or by repurchasing their shares. Obviously, every capital decision that

our investees have made has not benefitted us as shareholders, but overall we have garnered far more than

a dollar of value for each dollar they have retained. We consequently regard look-through earnings as

realistically portraying our yearly gain from operations.

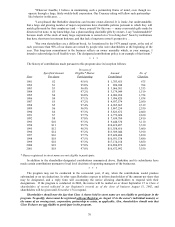

In 1992, our look-through earnings were $604 million, and in that same year we set a goal of raising them

by an average of 15% per annum to $1.8 billion in the year 2000. Since that time, however, we have issued

additional shares — including a significant number in the 1998 merger with General Re — so that we now

need look-through earnings of $2.4 billion in 2000 to match the per-share goal we originally were shooting

for. This is a target we still hope to hit.

7. We use debt sparingly and, when we do borrow, we attempt to structure our loans on a long-term fixed-

rate basis. We will reject interesting opportunities rather than over-leverage our balance sheet. This

conservatism has penalized our results but it is the only behavior that leaves us comfortable, considering

our fiduciary obligations to policyholders, lenders and the many equity holders who have committed

unusually large portions of their net worth to our care. (As one of the Indianapolis "500" winners said:

"To finish first, you must first finish.")

The financial calculus that Charlie and I employ would never permit our trading a good night's sleep for a

shot at a few extra percentage points of return. I've never believed in risking what my family and friends

have and need in order to pursue what they don't have and don't need.

Besides, Berkshire has access to two low-cost, non-perilous sources of leverage that allow us to safely own

far more assets than our equity capital alone would permit: deferred taxes and "float," the funds of others

that our insurance business holds because it receives premiums before needing to pay out losses. Both of

these funding sources have grown rapidly and now total about $32 billion.