Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 16

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 16 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

15

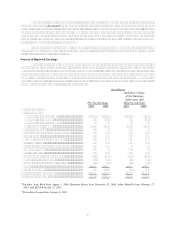

We made few changes in our portfolio during 2001. As a group, our larger holdings have performed

poorly in the last few years, some because of disappointing operating results. Charlie and I still like the basic

businesses of all the companies we own. But we do not believe Berkshires equity holdings as a group are

undervalued.

Our restrained enthusiasm for these securities is matched by decidedly lukewarm feelings about the

prospects for stocks in general over the next decade or so. I expressed my views about equity returns in a speech I

gave at an Allen and Company meeting in July (which was a follow-up to a similar presentation I had made two

years earlier) and an edited version of my comments appeared in a December 10th Fortune article. Im enclosing a

copy of that article. You can also view the Fortune version of my 1999 talk at our website

www.berkshirehathaway.com.

Charlie and I believe that American business will do fine over time but think that todays equity prices

presage only moderate returns for investors. The market outperformed business for a very long period, and that

phenomenon had to end. A market that no more than parallels business progress, however, is likely to leave many

investors disappointed, particularly those relatively new to the game.

Heres one for those who enjoy an odd coincidence: The Great Bubble ended on March 10, 2000 (though

we didnt realize that fact until some months later). On that day, the NASDAQ (recently 1,731) hit its all-time high

of 5,132. That same day, Berkshire shares traded at $40,800, their lowest price since mid-1997.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

During 2001, we were somewhat more active than usual in junk bonds. These are not, we should

emphasize, suitable investments for the general public, because too often these securities live up to their name. We

have never purchased a newly-issued junk bond, which is the only kind most investors are urged to buy. When

losses occur in this field, furthermore, they are often disastrous: Many issues end up at a small fraction of their

original offering price and some become entirely worthless.

Despite these dangers, we periodically find a few a very few junk securities that are interesting to us.

And, so far, our 50-year experience in distressed debt has proven rewarding. In our 1984 annual report, we

described our purchases of Washington Public Power System bonds when that issuer fell into disrepute. Weve

also, over the years, stepped into other apparent calamities such as Chrysler Financial, Texaco and RJR Nabisco

all of which returned to grace. Still, if we stay active in junk bonds, you can expect us to have losses from time to

time.

Occasionally, a purchase of distressed bonds leads us into something bigger. Early in the Fruit of the

Loom bankruptcy, we purchased the companys public and bank debt at about 50% of face value. This was an

unusual bankruptcy in that interest payments on senior debt were continued without interruption, which meant we

earned about a 15% current return. Our holdings grew to 10% of Fruits senior debt, which will probably end up

returning us about 70% of face value. Through this investment, we indirectly reduced our purchase price for the

whole company by a small amount.

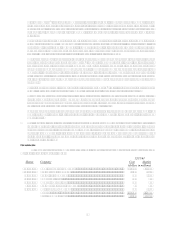

In late 2000, we began purchasing the obligations of FINOVA Group, a troubled finance company, and

that, too, led to our making a major transaction. FINOVA then had about $11 billion of debt outstanding, of which

we purchased 13% at about two-thirds of face value. We expected the company to go into bankruptcy, but believed

that liquidation of its assets would produce a payoff for creditors that would be well above our cost. As default

loomed in early 2001, we joined forces with Leucadia National Corporation to present the company with a

prepackaged plan for bankruptcy.

The plan as subsequently modified (and Im simplifying here) provided that creditors would be paid 70%

of face value (along with full interest) and that they would receive a newly-issued 7½% note for the 30% of their

claims not satisfied by cash. To fund FINOVAs 70% distribution, Leucadia and Berkshire formed a jointly-owned

entity mellifluently christened Berkadia that borrowed $5.6 billion through FleetBoston and, in turn, re-lent this

sum to FINOVA, concurrently obtaining a priority claim on its assets. Berkshire guaranteed 90% of the Berkadia

borrowing and also has a secondary guarantee on the 10% for which Leucadia has primary responsibility. (Did I

mention that I am simplifying?).