Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 7

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 7 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.6

Our operating companies made several bolt-on acquisitions during the year, and I cant resist telling you

about one. In December, Frank Rooney called to tell me H.H. Brown was buying the inventory and trademarks of

Acme Boot for $700,000.

That sounds like small potatoes. But would you believe it? Acme was the second purchase of P&R, an

acquisition that took place just before I left Graham-Newman in the spring of 1956. The price was $3.2 million,

part of it again paid with non-interest bearing notes, for a business with sales of $7 million.

After P&R merged with Northwest, Acme grew to be the worlds largest bootmaker, delivering annual

profits many multiples of what the company had cost P&R. But the business eventually hit the skids and never

recovered, and that resulted in our purchasing Acmes remnants.

In the frontispiece to Security Analysis, Ben Graham and Dave Dodd quoted Horace: Many shall be

restored that now are fallen and many shall fall that are now in honor. Fifty-two years after I first read those lines,

my appreciation for what they say about business and investments continues to grow.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

In addition to bolt-on acquisitions, our managers continually look for ways to grow internally. In that

regard, heres a postscript to a story I told you two years ago about R.C. Willeys move to Boise. As you may

remember, Bill Child, R.C. Willeys chairman, wanted to extend his home-furnishings operation beyond Utah, a

state in which his company does more than $300 million of business (up, it should be noted, from $250,000 when

Bill took over 48 years ago). The company achieved this dominant position, moreover, with a closed on Sunday

policy that defied conventional retailing wisdom. I was skeptical that this policy could succeed in Boise or, for that

matter, anyplace outside of Utah. After all, Sunday is the day many consumers most like to shop.

Bill then insisted on something extraordinary: He would invest $11 million of his own money to build the

Boise store and would sell it to Berkshire at cost (without interest!) if the venture succeeded. If it failed, Bill would

keep the store and eat the loss on its disposal. As I told you in the 1999 annual report, the store immediately

became a huge success ― and it has since grown.

Shortly after the Boise opening, Bill suggested we try Las Vegas, and this time I was even more skeptical.

How could we do business in a metropolis of that size and be closed on Sundays, a day that all of our competitors

would be exploiting? Buoyed by the Boise experience, however, we proceeded to locate in Henderson, a

mushrooming city adjacent to Las Vegas.

The result: This store outsells all others in the R.C. Willey chain, doing a volume of business that far

exceeds the volume of any competitor and that is twice what I had anticipated. I cut the ribbon at the grand opening

in October this was after a soft opening and a few weeks of exceptional sales and, just as I did at Boise, I

suggested to the crowd that the new store was my idea.

It didnt work. Today, when I pontificate about retailing, Berkshire people just say, What does Bill

think? (Im going to draw the line, however, if he suggests that we also close on Saturdays.)

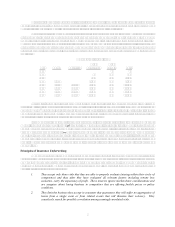

The Economics of Property/Casualty Insurance

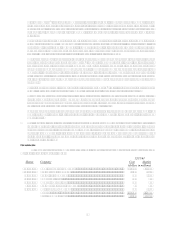

Our main business though we have others of great importance is insurance. To understand

Berkshire, therefore, it is necessary that you understand how to evaluate an insurance company. The key

determinants are: (1) the amount of float that the business generates; (2) its cost; and (3) most critical of all, the

long-term outlook for both of these factors.

To begin with, float is money we hold but don't own. In an insurance operation, float arises because

premiums are received before losses are paid, an interval that sometimes extends over many years. During that

time, the insurer invests the money. This pleasant activity typically carries with it a downside: The premiums that

an insurer takes in usually do not cover the losses and expenses it eventually must pay. That leaves it running an

"underwriting loss," which is the cost of float. An insurance business has value if its cost of float over time is less

than the cost the company would otherwise incur to obtain funds. But the business is a lemon if its cost of float is

higher than market rates for money.