Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 10

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 10 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.9

Why, you might ask, didnt I recognize the above facts before September 11th? The answer, sadly, is that I

did but I didnt convert thought into action. I violated the Noah rule: Predicting rain doesnt count; building arks

does. I consequently let Berkshire operate with a dangerous level of risk at General Re in particular. Im sorry to

say that much risk for which we havent been compensated remains on our books, but it is running off by the day.

At Berkshire, it should be noted, we have for some years been willing to assume more risk than any other

insurer has knowingly taken on. Thats still the case. We are perfectly willing to lose $2 billion to $2½ billion in a

single event (as we did on September 11th) if we have been paid properly for assuming the risk that caused the loss

(which on that occasion we werent).

Indeed, we have a major competitive advantage because of our tolerance for huge losses. Berkshire has

massive liquid resources, substantial non-insurance earnings, a favorable tax position and a knowledgeable

shareholder constituency willing to accept volatility in earnings. This unique combination enables us to assume

risks that far exceed the appetite of even our largest competitors. Over time, insuring these jumbo risks should be

profitable, though periodically they will bring on a terrible year.

The bottom-line today is that we will write some coverage for terrorist-related losses, including a few non-

correlated policies with very large limits. But we will not knowingly expose Berkshire to losses beyond what we

can comfortably handle. We will control our total exposure, no matter what the competition does.

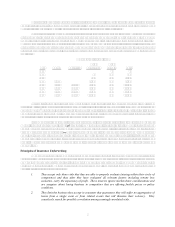

Insurance Operations in 2001

Over the years, our insurance business has provided ever-growing, low-cost funds that have fueled much

of Berkshires growth. Charlie and I believe this will continue to be the case. But we stumbled in a big way in

2001, largely because of underwriting losses at General Re.

In the past I have assured you that General Re was underwriting with discipline and I have been proven

wrong. Though its managers intentions were good, the company broke each of the three underwriting rules I set

forth in the last section and has paid a huge price for doing so. One obvious cause for its failure is that it did not

reserve correctly more about this in the next section and therefore severely miscalculated the cost of the product

it was selling. Not knowing your costs will cause problems in any business. In long-tail reinsurance, where years

of unawareness will promote and prolong severe underpricing, ignorance of true costs is dynamite.

Additionally, General Re was overly-competitive in going after, and retaining, business. While all

concerned may intend to underwrite with care, it is nonetheless difficult for able, hard-driving professionals to curb

their urge to prevail over competitors. If winning, however, is equated with market share rather than profits,

trouble awaits. No must be an important part of any underwriters vocabulary.

At the risk of sounding Pollyannaish, I now assure you that underwriting discipline is being restored at

General Re (and its Cologne Re subsidiary) with appropriate urgency. Joe Brandon was appointed General Res

CEO in September and, along with Tad Montross, its new president, is committed to producing underwriting

profits. Last fall, Charlie and I read Jack Welchs terrific book, Jack, Straight from the Gut (get a copy!). In

discussing it, we agreed that Joe has many of Jacks characteristics: He is smart, energetic, hands-on, and expects

much of both himself and his organization.

When it was an independent company, General Re often shone, and now it also has the considerable

strengths Berkshire brings to the table. With that added advantage and with underwriting discipline restored,

General Re should be a huge asset for Berkshire. I predict that Joe and Tad will make it so.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

At the National Indemnity reinsurance operation, Ajit Jain continues to add enormous value to Berkshire.

Working with only 18 associates, Ajit manages one of the worlds largest reinsurance operations measured by

assets, and the largest, based upon the size of individual risks assumed.

I have known the details of almost every policy that Ajit has written since he came with us in 1986, and

never on even a single occasion have I seen him break any of our three underwriting rules. His extraordinary

discipline, of course, does not eliminate losses; it does, however, prevent foolish losses. And thats the key: Just as

is the case in investing, insurers produce outstanding long-term results primarily by avoiding dumb decisions, rather

than by making brilliant ones.