Audi 2009 Annual Report Download - page 67

Download and view the complete annual report

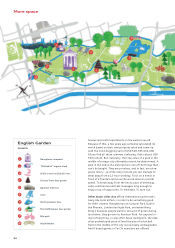

Please find page 67 of the 2009 Audi annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.More space

64

e came up with the storyline

for the international animated

hit film “Ratatouille” and is a

major role model for chefs all over the

world. But anyone who manages to

reserve a highly coveted table at one of

top U.S. chef Thomas Keller’s restau-

rants needs to steel themselves before

studying the menu. Instead of the usu-

al prestige dishes of a classic three-star

restaurant, they might find mussel

stew with bacon being served, or even

coffee and donuts. Keller, who runs two

of the six top-rated gastronomic estab-

lishments in the United States, New

York’s “Per Se” and the “French Laun-

dry” in California, likes to transform

typical everyday American fare such as

macaroni and cheese or cashew butter

and jam into an exquisite culinary

experience.

Until recently, such escapades would

have been unthinkable in Europe. Previ-

ously, the typical menu of a star-rated

restaurant had to feature lobster, caviar

or foie gras. The reason? “Because the

Michelin Guide expects us to use French

gourmet products.” That was the blunt

explanation offered by leading chef

Dieter Müller as recently as 2007 to ex-

plain why, apart from the Königsberger

Klopse meat balls with deep-fried ca-

pers on his renowned amuse-bouche

menu at Schlosshotel Lerbach in Ber-

gisch Gladbach, “unfortunately there

aren’t many regional specialties that

work in a three-star restaurant.”

Quite a lot has changed in the mean-

time. More and more top chefs all over

Europe are overturning the established

canon of prestige ingredients. And in

their vanguard are Germany’s elite

chefs, who are developing a repertoire

of home-style cooking capable at the

very least of holding its own alongside

the inevitable lobster, truffle and foie

gras – and prepared with superb crafts-

manship: Joachim Wissler from Ber-

gisch Gladbach puts a new slant on

lobscouse stew and cheesecake; at

“Sonnora” Helmut Thieltge serves a

variation on calf’s liver Berlin-style as

an amuse-gueule, while Sven Elverfeld

from Wolfsburg’s “Aqua” dares to put

cod with mixed pickles, sauté potatoes

and bacon on the menu.

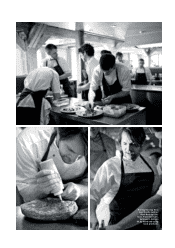

It is important to point out that all

these dishes bear little resemblance to

the rib-sticking fare on which they are

based, and in the hands of these top

chefs they are certainly on a par with

the haute cuisine old favorites such as

lobster thermidor and glazed blood-

stewed pigeon with foie gras and Alba

truffles. Even though their ingredients

seem simpler, they demand at least as

much concentration, culinary expertise,

and dedication to prepare. Assembling

them sometimes even demands much

more creativity than simply shaving a

100-euro truffle onto a plate – as Hol-

ger Stromberg, chef of the German soc-

cer team, well knows: “Unfortunately,

most young chefs coming to work for

me still assume that quality means a

high price tag. But the more costly the

produce they are let loose on, the slop-

pier they get.”

The main reason is the tradition of

chasing Michelin stars. The Michelin

Guide is an esteemed French institution

that focuses squarely on the cuisine

and luxury produce of its home country.

The gourmet branch of the tire manu-

facturer has been awarding its leg-

endary stars since 1926, according to

the same time-honored model, as a

guide to motorists with a penchant for

fine food: Three stars means a restau-

rant is “worth the trip,” two stars

means “worth a detour,” and one star

rates as “interesting.”

But even in the home of the connois-

seur, more and more gastronomes are

becoming “gastrosophes” and rejecting

all the toil and anguish of pursuing

three stars in favor of rediscovering the

pearls of traditional cuisine. Some of

them have even gone so far as to close

down a starred restaurant so that they

can start cooking precisely what they

want elsewhere, without the pressure.

The Breton master of fish and spices

Olivier Roellinger gave up his three

stars in November 2008, closing down

“Les Maisons de Bricourt” in Cancale,

France, held by many to be the best fish

restaurant in the world, so that he

could prepare similar dishes without all

the fuss at his second restaurant, “Le

Coquillage.” His fellow chef Alain Alex-

anian sold his star-winning “L’Alexan-

drin” in Lyon, France, in 2007 and has

since been touring regional producers

to research old recipes and methods of

preparation. He is using this lost and

now rediscovered knowledge in his ca-

pacity as gastro advisor with an organic

slant – for such clients as the “Hi Hotel”

in Nice, on the French Riviera, and the

public cafeteria of the St. Joseph Clinic

in Lyon, which uses exclusively organic

produce. “I want to offer the young

generation a new, healthy form of cui-

sine that is in harmony with the envi-

ronment and affordable.” The latter

motive also prompted Alain Senderens

to close his gourmet paradise, “Lucas

Carton,” after 28 years and to reposi-

tion himself with the “Senderens”

bistro: “I’ve lost my faith in a system

that leaves diners with a bill of 400

euros. From now on I want to do simple

cooking, without all the frills. I want

a restaurant that is in keeping with

the times but which still offers very

good quality and has a few surprising

innovations.”

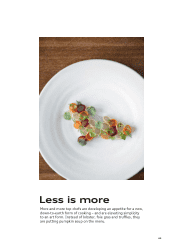

There is much more to this new desire

for simple cuisine than just a resur-

gence of what the Germans call “lux-

ese,” that modish blend of luxury and

asceticism that culminated in tawdry

concoctions such as curry wurst with

gold leaf and champagne. Rather, the

latest penchant for new luxury is more

likely to focus on transforming regional

products into delicacies using haute

cuisine skills: chops instead of Kobe

beef, and calf’s head instead of foie

gras. For all the differences between

their dishes and tastes, one belief

above all unites leading gourmands

“

Whoever dines in my restaurant should know that

they’ll only find such food in Copenhagen.”

René Redzepi, Michelin-starred chef in Copenhagen

COPY/PETER WAGNER

PHOTOS/DITTE ISAGER

H