Berkshire Hathaway 2002 Annual Report Download - page 8

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 8 of the 2002 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

7

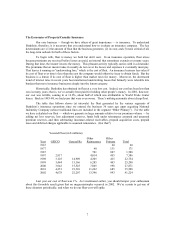

The Economics of Property/Casualty Insurance

Our core business — though we have others of great importance — is insurance. To understand

Berkshire, therefore, it is necessary that you understand how to evaluate an insurance company. The key

determinants are: (1) the amount of float that the business generates; (2) its cost; and (3) most critical of all,

the long-term outlook for both of these factors.

To begin with, float is money we hold but don't own. In an insurance operation, float arises

because premiums are received before losses are paid, an interval that sometimes extends over many years.

During that time, the insurer invests the money. This pleasant activity typically carries with it a downside:

The premiums that an insurer takes in usually do not cover the losses and expenses it eventually must pay.

That leaves it running an “underwriting loss,” which is the cost of float. An insurance business has value if

its cost of float over time is less than the cost the company would otherwise incur to obtain funds. But the

business is a lemon if its cost of float is higher than market rates for money. Moreover, the downward

trend of interest rates in recent years has transformed underwriting losses that formerly were tolerable into

burdens that move insurance businesses deeply into the lemon category.

Historically, Berkshire has obtained its float at a very low cost. Indeed, our cost has been less than

zero in many years; that is, we’ ve actually been paid for holding other people’ s money. In 2001, however,

our cost was terrible, coming in at 12.8%, about half of which was attributable to World Trade Center

losses. Back in 1983-84, we had years that were even worse. There’ s nothing automatic about cheap float.

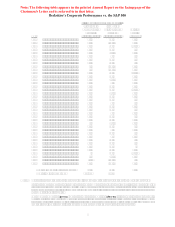

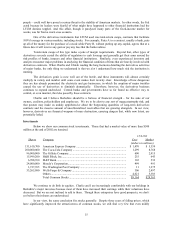

The table that follows shows (at intervals) the float generated by the various segments of

Berkshire’ s insurance operations since we entered the business 36 years ago upon acquiring National

Indemnity Company (whose traditional lines are included in the segment “Other Primary”). For the table

we have calculated our float — which we generate in large amounts relative to our premium volume — by

adding net loss reserves, loss adjustment reserves, funds held under reinsurance assumed and unearned

premium reserves, and then subtracting insurance-related receivables, prepaid acquisition costs, prepaid

taxes and deferred charges applicable to assumed reinsurance. (Got that?)

Yearend Float (in $ millions)

Other Other

Year GEICO General Re Reinsurance Primary Total

1967 20 20

1977 40 131 171

1987 701 807 1,508

1997 2,917 4,014 455 7,386

1998 3,125 14,909 4,305 415 22,754

1999 3,444 15,166 6,285 403 25,298

2000 3,943 15,525 7,805 598 27,871

2001 4,251 19,310 11,262 685 35,508

2002 4,678 22,207 13,396 943 41,224

Last year our cost of float was 1%. As I mentioned earlier, you should temper your enthusiasm

about this favorable result given that no megacatastrophe occurred in 2002. We’ re certain to get one of

these disasters periodically, and when we do our float-cost will spike.