Berkshire Hathaway 1998 Annual Report Download - page 64

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 64 of the 1998 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.63

I made a similar statement in our 1983 Annual Report about the goodwill attributed to See's Candy, when

I used that company as an example in a discussion of goodwill accounting. At that time, our balance sheet carried

about $36 million of See's goodwill. We have since been charging about $1 million against earnings every year in

order to amortize the asset, and the See's goodwill on our balance sheet is now down to about $21 million. In other

words, from an accounting standpoint, See's is now presented as having lost a good deal of goodwill since 1983.

The economic facts could not be more different. In 1983, See's earned about $27 million pre-tax on $11

million of net operating assets; in 1997 it earned $59 million on $5 million of net operating assets. Clearly See's

economic goodwill has increased dramatically during the interval rather than decreased. Just as clearly, See's is worth

many hundreds of millions of dollars more than its stated value on our books.

We could, of course, be wrong, but we expect that GEICO's gradual loss of accounting value will continue

to be paired with major increases in its economic value. Certainly that has been the pattern at most of our subsidiaries,

not just See's. That is why we regularly present our operating earnings in a way that allows you to ignore all purchase-

accounting adjustments.

Before leaving this subject, we should issue an important warning: Investors are often led astray by CEOs

and Wall Street analysts who equate depreciation charges with the amortization charges we have just discussed. In

no way are the two the same: With rare exceptions, depreciation is an economic cost every bit as real as wages,

materials, or taxes. Certainly that is true at Berkshire and at virtually all the other businesses we have studied.

Furthermore, we do not think so-called EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is

a meaningful measure of performance. Managements that dismiss the importance of depreciation — and emphasize

"cash flow" or EBITDA — are apt to make faulty decisions, and you should keep that in mind as you make your own

investment decisions.

THE MANAGING OF BERKSHIRE

I think it's appropriate that I conclude with a discussion of Berkshire's management, today and in the future.

As our first owner-related principle tells you, Charlie and I are the managing partners of Berkshire. But we

subcontract all of the heavy lifting in this business to the managers of our subsidiaries. In fact, we delegate almost

to the point of abdication: Though Berkshire has about 45,000 employees, only 12 of these are at headquarters.

Charlie and I mainly attend to capital allocation and the care and feeding of our key managers. Most of these

managers are happiest when they are left alone to run their businesses, and that is customarily just how we leave them.

That puts them in charge of all operating decisions and of dispatching the excess cash they generate to headquarters.

By sending it to us, they don't get diverted by the various enticements that would come their way were they

responsible for deploying the cash their businesses throw off. Furthermore, Charlie and I are exposed to a much wider

range of possibilities for investing these funds than any of our managers could find in his or her own industry.

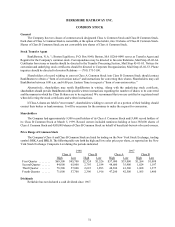

Most of our managers are independently wealthy, and it's therefore up to us to create a climate that

encourages them to choose working with Berkshire over golfing or fishing. This leaves us needing to treat them fairly

and in the manner that we would wish to be treated if our positions were reversed.

As for the allocation of capital, that's an activity both Charlie and I enjoy and in which we have acquired

some useful experience. In a general sense, grey hair doesn't hurt on this playing field: You don't need good hand-

eye coordination or well-toned muscles to push money around (thank heavens). As long as our minds continue to

function effectively, Charlie and I can keep on doing our jobs pretty much as we have in the past.