JetBlue Airlines 2010 Annual Report Download - page 80

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 80 of the 2010 JetBlue Airlines annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.of operating in the airline industry and/or economic downturns, which may in turn have a negative impact on

our business.

Under certain of our LiveTV third party agreements, as well as our aircraft operating lease agreements,

we are required to restore certain property or equipment to its original form upon expiration of the related

agreement. We have recorded the estimated fair value of these retirement obligations, which was not

significant as of December 31, 2010, but may increase over time.

Many aspects of airlines’ operations are subject to increasingly stringent federal, state, local, and foreign

laws protecting the environment. There is growing consensus that some form of regulation will be forthcoming

at the federal level with respect to greenhouse gas emissions (including carbon dioxide (CO

2

)) and such

regulation could result in the creation of substantial additional costs in the form of taxes or emission

allowances. Since the domestic airline industry is increasingly price sensitive, we may not be able to recover

the cost of compliance with new or more stringent environmental laws and regulations from our passengers,

which could adversely affect our business. Although it is not expected that the costs of complying with current

environmental regulations will have a material adverse effect on our financial position, results of operations or

cash flows, no assurance can be made that the costs of complying with environmental regulations in the future

will not have such an effect. The impact to us and our industry from such actions is likely to be adverse and

could be significant, particularly if regulators were to conclude that emissions from commercial aircraft cause

significant harm to the upper atmosphere or have a greater impact on climate change than other industries.

In December 2009, the DOT issued a series of passenger protection rules which, among other things,

impose tarmac delay limits for U.S. airline domestic flights. The rules became effective in April 2010, and

require U.S. airlines to allow passengers to deplane after three hours on the tarmac, with certain safety and

security exceptions. Violators can face fines up to a maximum of $27,500 per passenger. The new rules also

introduce requirements to disclose on-time performance and delay statistics for certain flights. These new rules

may have adverse consequences on our business and our results of operations.

We are unable to estimate the potential amount of future payments under the foregoing indemnities and

agreements.

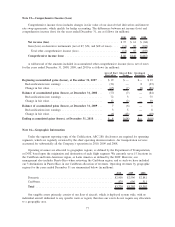

Note 13—Financial Derivative Instruments and Risk Management

As part of our risk management strategy, we periodically purchase crude or heating oil option contracts or

swap agreements to manage our exposure to the effect of changes in the price and availability of aircraft fuel.

Prices for these commodities are normally highly correlated to aircraft fuel, making derivatives of them

effective at providing short-term protection against sharp increases in average fuel prices. We also periodically

enter into jet fuel swaps, as well as basis swaps for the differential between heating oil and jet fuel, to further

limit the variability in fuel prices at various locations. To manage the variability of the cash flows associated

with our variable rate debt, we have also entered into interest rate swaps. We do not hold or issue any

derivative financial instruments for trading purposes.

Aircraft fuel derivatives: We attempt to obtain cash flow hedge accounting treatment for each aircraft

fuel derivative that we enter into. This treatment is provided for under the Derivatives and Hedging topic of

the Codification, which allows for gains and losses on the effective portion of qualifying hedges to be deferred

until the underlying planned jet fuel consumption occurs, rather than recognizing the gains and losses on these

instruments into earnings for each period they are outstanding. The effective portion of realized aircraft fuel

hedging derivative gains and losses is recognized in fuel expense. Ineffectiveness results, in certain

circumstances, when the change in the total fair value of the derivative instrument differs from the change in

the value of our expected future cash outlays for the purchase of aircraft fuel and is recognized in interest

income and other immediately. Likewise, if a hedge does not qualify for hedge accounting, the periodic

changes in its fair value are recognized in interest income and other in the period of the change. When aircraft

fuel is consumed and the related derivative contract settles, any gain or loss previously recorded in other

comprehensive income is recognized in aircraft fuel expense. All cash flows related to our fuel hedging

derivatives are classified as operating cash flows.

71