Berkshire Hathaway 1999 Annual Report Download - page 6

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 6 of the 1999 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.5

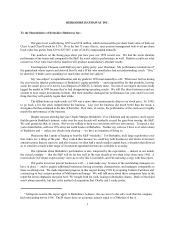

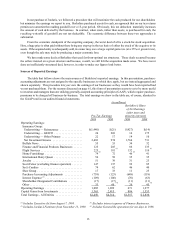

You should be aware that one item regularly working to widen the amount by which intrinsic value exceeds book

value is the annual charge against income we take for amortization of goodwill — an amount now running about $500

million. This charge reduces the amount of goodwill we show as an asset and likewise the amount that is included in

our book value. This is an accounting matter having nothing to do with true economic goodwill, which increases in most

years. But even if economic goodwill were to remain constant, the annual amortization charge would persistently widen

the gap between intrinsic value and book value.

Though we can’t give you a precise figure for Berkshire’s intrinsic value, or even an approximation, Charlie and

I can assure you that it far exceeds our $57.8 billion book value. Businesses such as See’s and Buffalo News are now

worth fifteen to twenty times the value at which they are carried on our books. Our goal is to continually widen this

spread at all subsidiaries.

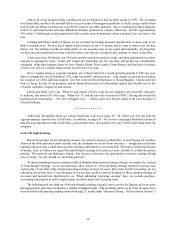

A Managerial Story You Will Never Read Elsewhere

Berkshire’s collection of manag ers is unusual in several important ways. As one example, a very high percentage

of these men and women are independently wealthy, having made fortunes in the businesses that they run. They work

neither because they need the money nor because they are contractually obligated to — we have no contracts at Berkshire.

Rather, they work long and hard because they love their businesses. And I use the word “their” advisedly, since these

managers are truly in charge — there are no show-and-tell presentations in Omaha, no budgets to be approved by

headquarters, no dictums issued about capital expenditures. We simply ask our managers to run their companies as if

these are the sole asset of their families and will remain so for the next century.

Charlie and I try to behave with our managers just as we attempt to behave with Berkshire’s shareholders, treating

both groups as we would wish to be treated if our positions were reversed. Though “working” means nothing to me

financially, I love doing it at Berkshire for some simple reasons: It gives me a sense of achievement, a freedom to act as

I see fit and an opportunity to interact daily with people I like and trust. Why should our managers — accomplished

artists at what they do — see things differently?

In their relations with Berkshire, our managers often appear to be hewing to President Kennedy’s charge, “Ask

not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” Here’s a remarkable story from last year:

It’s about R. C. Willey, Utah’s dominant home furnishing business, which Berkshire purchased from Bill Child and his

family in 1995. Bill and most of his managers are Mormons, and for this reason R. C. Willey’s stores have neve r

operated on Sunday. This is a difficult way to do business: Sunday is the favorite shopping day for many customers.

Bill, nonetheless, stuck to his principles -- and while doing so built his business from $250,000 of annual sales in 1954,

when he took over, to $342 million in 1999.

Bill felt that R. C. Willey could operate successfully in markets outside of Utah and in 1997 suggested that we open

a store in Boise. I was highly skeptical about taking a no-Sunday policy into a new territory where we would be up

against entrenched rivals open seven days a week. Nevertheless, this was Bill’s business to run. So, despite m y

reservations, I told him to follow both his business judgment and his religious convictions.

Bill then insisted on a truly extraordinary proposition: He would personally buy the land and build the store — for

about $9 million as it turned out — and would sell it to us at his cost if it proved to be successful. On the other hand,

if sales fell short of his expectations, we could exit the business without paying Bill a cent. This outcome, of course, would

leave him with a huge investment in an empty building. I told him that I appreciated his offer but felt that if Berkshire

was going to get the upside it should also take the downside. Bill said nothing doing: If there was to be failure because

of his religious beliefs, he wanted to take the blow personally.

The store opened last August and immediately became a huge success. Bill thereupon turned the property over

to us — including some extra land that had appreciated significantly — and we wrote him a check for his cost. And get

this: Bill refused to take a dime of interest on the capital he had tied up over the two years.