Berkshire Hathaway 1999 Annual Report Download - page 11

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 11 of the 1999 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.10

now are taking delivery of about 8% of all business jets manufactured in the world, and we wish we could get a bigger

share than that. Though EJA was supply-constrained in 1999, its recurring revenues — monthly management fees plus

hourly flight fees — increased 46%.

The fractional-ownership industry is still in its infancy. EJA is now building critical mass in Europe, and over

time we will expand around the world. Doing that will be expensive — very expensive — but we will spend what it

takes. Scale is vital to both us and our customers: The company with the most planes in the air worldwide will be able

to offer its customers the best service. “Buy a fraction, get a fleet” has real meaning at EJA.

EJA enjoys another important advantage in that its two largest competitors are both subsidiaries of aircraft

manufacturers and sell only the aircraft their parents make. Though these are fine planes, these competitors are severely

limited in the cabin styles and mission capabilities they can offer. EJA, in contrast, offers a wide array of planes from

five suppliers. Consequently, we can give the customer whatever he needs to buy — rather than his getting what the

competitor’s parent needs to sell.

Last year in this report, I described my family’s delight with the one-quarter (200 flight hours annually) of a

Hawker 1000 that we had owned since 1995. I got so pumped up by my own prose that shortly thereafter I signed up

for one-sixteenth of a Cessna V Ultra as well. Now my annual outlays at EJA and Borsheim’s, combined, total ten times

my salary. Think of this as a rough guideline for your own expenditures with us.

During the past year, two of Berkshire’s outside directors have also signed on with EJA. (Maybe we’re paying

them too much.) You should be aware that they and I are charged exactly the same price for planes and service as is

any other customer: EJA follows a “most favored nations” policy, with no one getting a special deal.

And now, brace yourself. Last year, EJA passed the ultimate test: Charlie signed up. No other endorsement could

speak more eloquently to the value of the EJA service. Give us a call at 1-800-848-6436 and ask for our “white paper”

on fractional ownership.

Acquisitions of 1999

At both GEICO and Executive Jet, our best source of new customers is the happy ones we already have. Indeed,

about 65% of our new owners of aircraft come as referrals from current owners who have fallen in love with the service.

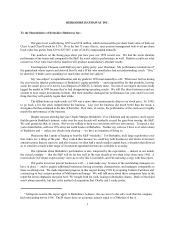

Our acquisitions usually develop in the same way. At other companies, executives may devote themselves to

pursuing acquisition possibilities with investment bankers, utilizing an auction process that has become standardized.

In this exercise the bankers prepare a “book” that makes me think of the Superman comics of my youth. In the Wall

Street version, a formerly mild-mannered company emerges from the investment banker’s phone booth able to leap over

competitors in a single bound and with earnings moving faster than a speeding bullet. Titillated by the book’ s

description of the acquiree’s powers, acquisition-hungry CEOs — Lois Lanes all, beneath their cool exteriors —

promptly swoon.

What’s particularly entertaining i n these books is the precision with which earnings are projected for many years

ahead. If you ask the author-banker, however, what his own firm will earn next month, he will go into a protective

crouch and tell you that business and markets are far too uncertain for him to venture a forecast.

Here’s one story I can’t resist relat ing: In 1985, a major investment banking house undertook to sell Scott Fetzer,

offering it widely — but with no success. Upon reading of this strikeout, I wrote Ralph Schey, then and now Scott

Fetzer’s CEO, expressin g an interest in buying the business. I had never met Ralph, but within a week we had a deal.

Unfortunately, Scott Fetzer’s l etter of engagement with the banking firm provided it a $2.5 million fee upon sale, even

if it had nothing to do with finding the buyer. I guess the lead banker felt he should do something for his payment, so

he graciously offered us a copy of the book on Scott Fetzer that his firm had prepared. With his customary tact, Charlie

responded: “I’ll pay $2.5 million not to read it.”

At Berkshire, our carefully-crafted acquisition strategy is simply to wait for the phone to ring. Happily, it

sometimes does so, usually because a manager who sold to us earlier has recommended to a friend that he think about

following suit.