Spirit Airlines 2013 Annual Report Download - page 40

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 40 of the 2013 Spirit Airlines annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.40

Aircraft Fuel. Fuel costs represent the single largest operating expense for most airlines, including ours. Fuel costs have

been subject to wide price fluctuations in recent years. Fuel availability and pricing are also subject to refining capacity, periods

of market surplus and shortage and demand for heating oil, gasoline and other petroleum products, as well as meteorological,

economic and political factors and events occurring throughout the world, which we can neither control nor accurately predict.

We source a significant portion of our fuel from refining resources located in the southeast United States, particularly facilities

adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico. Gulf Coast fuel is subject to volatility and supply disruptions, particularly in hurricane season

when refinery shutdowns have occurred in recent years, or when the threat of weather-related disruptions has caused Gulf

Coast fuel prices to spike above other regional sources. Both jet fuel swaps and jet fuel options are used at times to protect the

refining price risk between the price of crude oil and the price of refined jet fuel, and to manage the risk of increasing fuel

prices. Historically, we have protected approximately 70% of our forecasted fuel requirements during peak hurricane season

(August through October) using jet fuel swaps. Our fuel hedging practices are dependent upon many factors, including our

assessment of market conditions for fuel, our access to the capital necessary to support margin requirements, the pricing of

hedges and other derivative products in the market, our overall appetite for risk and applicable regulatory policies. As of

December 31, 2013, we had no derivative contracts outstanding. As of December 31, 2013, we purchased all of our aircraft fuel

under a single fuel service contract. The cost and future availability of jet fuel cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty.

Labor. The airline industry is heavily unionized. The wages, benefits and work rules of unionized airline industry

employees are determined by collective bargaining agreements, or CBAs. Relations between air carriers and labor unions in the

United States are governed by the RLA. Under the RLA, CBAs generally contain “amendable dates” rather than expiration

dates, and the RLA requires that a carrier maintain the existing terms and conditions of employment following the amendable

date through a multi-stage and usually lengthy series of bargaining processes overseen by the NMB. This process continues

until either the parties have reached agreement on a new CBA, or the parties have been released to “self-help” by the NMB. In

most circumstances, the RLA prohibits strikes; however, after release by the NMB, carriers and unions are free to engage in

self-help measures such as strikes and lockouts.

We have three union-represented employee groups comprising approximately 59% of our employees at December 31,

2013. Our pilots are represented by the Airline Pilots Association, International or ALPA, our flight attendants are represented

by the Association of Flight Attendants, or AFA-CWA, and our flight dispatchers are represented by the Transport Workers

Union of America, or TWU. Conflicts between airlines and their unions can lead to work slowdowns or stoppages. In June

2010, we experienced a five-day strike by our pilots, which caused us to shut down our flight operations. The strike ended as a

result of our reaching a tentative agreement under a Return to Work Agreement and a full flight schedule was resumed on

June 18, 2010. On August 1, 2010, we entered into a five-year collective bargaining agreement with our pilots. In August 2013,

we entered into a five-year agreement with our flight dispatchers. In December 2013, with the help of the NMB, we reached a

tentative agreement for a five-year contract with our flight attendants. The tentative agreement was subject to ratification by the

flight attendant membership. On February 7, 2014, we were notified that the flight attendants voted to not ratify the tentative

agreement. We will continue to work together with the AFA and the NMB with a goal of reaching a mutually beneficial

agreement. We believe the five-year term of our CBAs is valuable in providing stability to our labor costs and provide us with

competitive labor costs compared to other U.S.-based low-cost carriers. If we are unable to reach agreement with any of our

unionized work groups in current or future negotiations regarding the terms of their CBAs, we may be subject to work

interruptions or stoppages, such as the strike by our pilots in June 2010. A strike or other significant labor dispute with our

unionized employees is likely to adversely affect our ability to conduct business.

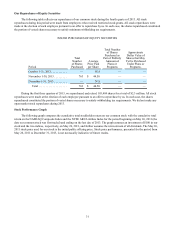

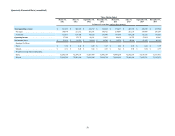

Maintenance Expense. Maintenance expense grew through 2013, 2012 and 2011 mainly as a result of the increasing age

(approximately 5.1 years on average at December 31, 2013) and size of our fleet. As the fleet ages, we expect that maintenance

costs will increase in absolute terms. The amount of total maintenance costs and related amortization of heavy maintenance

(included in depreciation and amortization expense) is subject to many variables such as future utilization rates, average stage

length, the size and makeup of the fleet in future periods and the level of unscheduled maintenance events and their actual

costs. Accordingly, we cannot reliably quantify future maintenance expenses for any significant period of time. However, we

believe, based on our scheduled maintenance events, maintenance expense and maintenance-related amortization expense in

2014 will be approximately $113 million. In addition, we expect to capitalize $40 million of costs for heavy maintenance

during 2014.

As a result of a significant portion of our fleet being acquired over a relatively short period of time, significant

maintenance scheduled on each of our planes will occur at roughly the same time, meaning we will incur our most expensive

scheduled maintenance obligations across our current fleet around the same time. These more significant maintenance activities

will result in out-of-service periods during which our aircraft will be dedicated to maintenance activities and unavailable to fly

revenue service. In addition, management expects that the final heavy maintenance events will be amortized over the remaining

lease term rather than until the next estimated heavy maintenance event, because we account for heavy maintenance under the

deferral method. This will result in significantly higher depreciation and amortization expense related to heavy maintenance in