Audi 2007 Annual Report Download - page 43

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 43 of the 2007 Audi annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

Today, driving a car is not much harder than riding a street car

or a bike. Any kid can do it. Cars are so stuffed with electron-

ics that the driver hardly knows what’s going on underneath

the hood. Under socialism, driving was a challenge, a test.

Anyone who was able to drive a car in Communist Russia

would probably have had no trouble flying a plane had he

needed to. The only thing that Communist drivers had over

their Western counterparts was that they never had trouble

finding a parking space.

80 families used to live in our Moscow apartment block.

There were three cars in the parking lot. One of them, a yel-

low Moskvitch, belonged to my friend Andrej, an unusually

young driver by Soviet standards. Officially, the car belonged

to his grandfather, a war veteran who had received a whole

string of medals, including the highest accolade: A star that

marked him out as a Hero of the Soviet Union. War veterans

were eligible for discounts when they bought cars, but they

had to be prepared for a long wait, just like everyone else.

Andrej’s grandfather most likely joined the queue for a car in

1945, right after the end of World War II. Decades later, he

had forgotten his dream of a car, when suddenly, just before

his 80th birthday, he received a call telling him he could pick

up the car allocated to him. “Come to Branch Number 108 on

Friday at nine o’clock and don’t forget your 12,000 roubles!”

trilled a friendly female at the other end of the line.

The call came too late. Gramps was too old to drive, and the

car – a Moskvitch – was much too expensive for the family.

12,000 roubles was a lot of money. But his grandson was over-

whelmed at the thought of owning a car. Such an unprecedent-

ed rise in living standards would make the girls look at him in

a completely different light. He discussed the subject at length

with his grandfather, received his blessing and his savings,

plundered the family piggy bank, borrowed from everyone he

knew, and even tracked down a distant relative, a successful

party official, his mother’s cousin, who lent him the missing

4,000 roubles despite never having set eyes on the boy in his

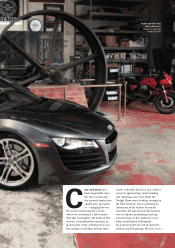

Rapid Russians

Author Wladimir Kaminer knows how to put a quaint comic

slant on everyday life. In an exclusive for the Audi Annual

Report, he writes about Russia’s love affair with fast cars.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Wladimir Kaminer, born in Moscow (1967), came to

Berlin in 1990 from the former Soviet Union. At the

“Kaffee Burger” dance club, he regularly held a

“Russian disco” – now a firm favorite among Berlin

clubbers. “Russendisko“ was also the name of his

first short story collection, that took him to the top

of the bestseller lists. In 2007 his eleventh book,

“Ich bin kein Berliner,” was published.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

uring the 1980s, Russia was still a pedestri-

an’s paradise. Even in Moscow, you could

quite happily cross any street on a red light

with your eyes closed. Your chances of being

knocked down were no greater than the odds of winning a car

in the lottery. The cheapest Soviet-era passenger car cost about

the same as an engineer would earn – in three years.

And as for life expectancy under socialism, it was low. So you

hardly stood a chance of legally earning enough money within

your short lifetime. Barring a few exceptions.

The first exception was the “Sports Lottery.” If you got six

numbers right out of 49, you won a car. The second exception

was a five-year contract to conquer Siberia with an accom-

panying savings plan. Anyone who signed up to this agreement

had to toil away for five years building the world’s longest

railway – the Baikal-Amur line. Having served his time, he’d

receive an apartment, or a car.

The third possibility for would-be car owners was to embark

on a career in the Communist party, and with a bit of luck at

some point they would receive an official black Volga – com-

plete with chauffeur. You could also marry a rich KGB widow.

But all these methods belong to the realm of theory. Soviet

reality looked somewhat different: To win in the lottery, you

needed to be really lucky, while working on the Baikal-Amur

line meant your nose was likely to freeze off, and rich KGB

widows weren’t something you ran into every day of the week.

Because of all this, motorists, in Soviet times, were in a caste

of their own.

They were secretive folks each of whom, in his own way,

had signed a pact with the devil, and, as penance, had to suffer

his carless neighbors’ envy and glee forever afterwards. Life

for the car driver was far more complicated than it was for

pedestrians. During the week, drivers would set their alarm

clocks about an hour earlier than pedestrians to prepare their

Ladas and Moskvitches for the journey. At weekends, when

the rest of civilized society was at home in front of the TV,

relaxing with their friends in the sauna or going out to catch a

movie, motorists would lie underneath their vehicles, screw-

driver in hand. Spending weekends toiling in the garage be-

came a part of their lifestyle – more so than the actual driving.

Soviet makes of car were not simply new or used, in good

working order or broken down. They possessed the ability to

be both at the same time. When new, they were already used.

Never in perfect working order, they never broke down com-

pletely. And each driver became a first-class mechanic simply

out of necessity.

D