Pfizer 2013 Annual Report Download - page 7

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 7 of the 2013 Pfizer annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

Financial Review

Pfizer Inc. and Subsidiary Companies

6

2013 Financial Report

Under the U.S. Healthcare Legislation, biosimilar applications may not be submitted until four years after the approval of the reference,

innovator biologic. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for implementation of the legislation, which will require

the FDA to address such key topics as the type and extent of data needed to establish biosimilarity; the data required to achieve

interchangeability compared to biosimilarity; the naming convention for biosimilars; the tracking and tracing of adverse events; and the

acceptability of data using a non-U.S. licensed comparator to demonstrate biosimilarity and/or interchangeability with a U.S.-licensed

reference product. The FDA has begun to address some of these issues with the February 2012 release of three draft guidance

documents. Specifically, the FDA has clarified that biosimilar applicants may use a non-U.S.-licensed comparator in certain studies to

support a demonstration of biosimilarity to a U.S.-licensed reference product. Over the next several years, the FDA is expected to finalize

the guidance documents released in 2012 and issue new draft guidance on clinical pharmacology for biosimilars. If competitors are able

to obtain marketing approval for biosimilars referencing our biotechnology products, our biotechnology products may become subject to

competition from biosimilars, with attendant competitive pressure, and price reductions could follow. Expiration or successful challenge of

applicable patent rights could trigger this competition, assuming any relevant exclusivity period has expired. However, biosimilar

manufacturing is complex and biosimilars are not necessarily identical to the reference products. Therefore, at least initially upon

approval of a biosimilar competitor, biosimilar competition with respect to biologics may not be as significant as generic competition with

respect to small molecule drugs. As part of our business strategy, we are capitalizing on our expertise in biologics manufacturing, as well

as our regulatory and commercial strengths, to develop biosimilar medicines. As such, a better-defined biosimilars approval pathway will

assist us in pursuing approval of our own biosimilar products in the U.S.

Regulatory Environment/Pricing and Access––U.S. Government and Other Payer Group Pressures

Governments, managed care organizations and other payer groups continue to seek increasing discounts on our products through a variety of

means, such as leveraging their purchasing power, implementing price controls, and demanding price cuts (directly or by rebate actions). In

particular, we continue to face widespread downward pressures on international pricing and reimbursement, particularly in developed

European markets, Japan and in certain emerging markets, all of which have a large government share of pharmaceutical spending and are

facing a difficult fiscal environment. Specific pricing pressures in 2013 included measures to reduce pharmaceutical prices and expenditures in

Japan, France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Belgium, Ireland and Portugal. For additional information, see the “Government Regulation and Price

Constraints––Outside the United States––Pricing and Reimbursement” section of our 2013 Annual Report on Form 10-K. Also, health insurers

and benefit plans continue to limit access to certain of our medicines by imposing formulary restrictions in favor of the increased use of

generics. In prior years, Presidential advisory groups tasked with reducing healthcare spending have recommended and legislative changes

have been proposed that would allow the U.S. government to directly negotiate prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers on behalf of

Medicare beneficiaries, which we expect would restrict access to and reimbursement for our products.

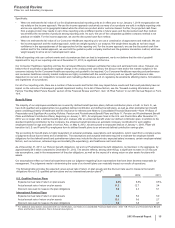

Specifically, in the U.S., the following government activities have potential impacts on our financial results:

• Budget Control Act of 2011—In August 2011, the federal Budget Control Act of 2011 (the Budget Control Act) was enacted in the U.S. The

Budget Control Act includes provisions to raise the U.S. Treasury Department's borrowing limit, known as the debt ceiling, and provisions

to reduce the federal deficit by $2.4 trillion between 2012 and 2021. Deficit-reduction targets included $900 billion of discretionary

spending reductions associated with the Department of Health and Human Services and various agencies charged with national security,

but those discretionary spending reductions do not include programs such as Medicare and Medicaid or direct changes to

pharmaceutical pricing, rebates or discounts. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) was responsible for identifying the remaining

$1.5 trillion of deficit reductions, which were divided evenly between defense and non-defense spending. The Budget Control Act

spending reductions to date have not had a material adverse impact on our results of operations.

In December 2013, Congress enacted minor amendments to the Budget Control Act, providing for greater discretionary spending in 2014

and 2015 than originally budgeted. The amendments also provide for FDA user fee sequester relief for two years, allowing the FDA to

continue to review new products. The new legislation continues to prohibit reductions in payments to Medicare providers from exceeding

a 2% reduction of the originally budgeted amount, and extends this prohibition for two years (until 2023). The implications to Pfizer of

these changes are expected to be nominal. However, any significant spending reductions affecting Medicare, Medicaid or other publicly

funded or subsidized health programs that may be implemented, and/or any significant additional taxes or fees that may be imposed on

us, as part of any broader deficit-reduction effort or legislative replacement for the Budget Control Act, could have an adverse impact on

our results of operations.

• Sustainable Growth Rate Replacement—The Medicare physician payment formula known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) is

routinely overridden by Congressional action because it would lead to dramatic decreases in physician payment. Congress issued a bi-

partisan proposal to repeal the SGR and replace it with a new payment model. The proposed fee-for-service system would provide a

modest annual payment rate increase until 2018, while allowing physicians and healthcare professionals to earn performance-based

incentive payments after 2018. This form of SGR replacement is estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to cost the federal

government approximately $130 billion over 10 years. The source of those funds has yet to be determined, but could include additional

taxes on and/or rebate requirements applicable to the pharmaceutical industry, including Pfizer. Congress is considering a bill and is

working to identify the means to pay for it prior to March 31, 2014, when the current SGR will expire.

• Federal Debt Ceiling—After the U.S. federal debt ceiling was reached on May 19, 2013 and measures taken by the U.S. Treasury

Department to enable the U.S. federal government to continue meeting its financial obligations were nearly exhausted, Congress enacted

legislation on October 16, 2013 that suspended the debt ceiling through February 7, 2014 and preserved the ability of the U.S. Treasury

Department to use “extraordinary measures” to avoid a default on U.S. federal government debt for a short period of time thereafter. In

February 2014, Congress enacted legislation that further suspends the debt ceiling until March 15, 2015, effectively ensuring the U.S.

federal government’s ability to satisfy its financial obligations until that date, including under Medicare, Medicaid and other publicly funded

or subsidized health programs that have a direct impact on our results of operations.

As the healthcare cost growth rate in the U.S. continues to outpace inflation, cost-reduction and access pressures are increasing in intensity.

Containing entitlement spending, including Medicare and Medicaid, is a major focus of deficit-reduction efforts. The ACA, which expanded the