Berkshire Hathaway 2012 Annual Report Download - page 22

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 22 of the 2012 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.But never forget: In repurchase decisions, price is all-important. Value is destroyed when purchases are

made above intrinsic value. The directors and I believe that continuing shareholders are benefitted in a meaningful

way by purchases up to our 120% limit.

And that brings us to dividends. Here we have to make a few assumptions and use some math. The

numbers will require careful reading, but they are essential to understanding the case for and against dividends. So

bear with me.

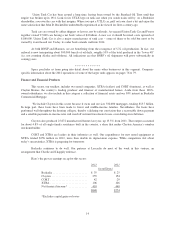

We’ll start by assuming that you and I are the equal owners of a business with $2 million of net worth. The

business earns 12% on tangible net worth – $240,000 – and can reasonably expect to earn the same 12% on

reinvested earnings. Furthermore, there are outsiders who always wish to buy into our business at 125% of net

worth. Therefore, the value of what we each own is now $1.25 million.

You would like to have the two of us shareholders receive one-third of our company’s annual earnings and

have two-thirds be reinvested. That plan, you feel, will nicely balance your needs for both current income and

capital growth. So you suggest that we pay out $80,000 of current earnings and retain $160,000 to increase the

future earnings of the business. In the first year, your dividend would be $40,000, and as earnings grew and the one-

third payout was maintained, so too would your dividend. In total, dividends and stock value would increase 8%

each year (12% earned on net worth less 4% of net worth paid out).

After ten years our company would have a net worth of $4,317,850 (the original $2 million compounded at

8%) and your dividend in the upcoming year would be $86,357. Each of us would have shares worth $2,698,656

(125% of our half of the company’s net worth). And we would live happily ever after – with dividends and the

value of our stock continuing to grow at 8% annually.

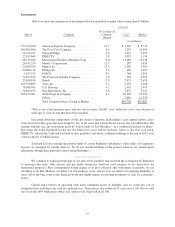

There is an alternative approach, however, that would leave us even happier. Under this scenario, we

would leave all earnings in the company and each sell 3.2% of our shares annually. Since the shares would be sold

at 125% of book value, this approach would produce the same $40,000 of cash initially, a sum that would grow

annually. Call this option the “sell-off” approach.

Under this “sell-off” scenario, the net worth of our company increases to $6,211,696 after ten years

($2 million compounded at 12%). Because we would be selling shares each year, our percentage ownership would

have declined, and, after ten years, we would each own 36.12% of the business. Even so, your share of the net

worth of the company at that time would be $2,243,540. And, remember, every dollar of net worth attributable to

each of us can be sold for $1.25. Therefore, the market value of your remaining shares would be $2,804,425, about

4% greater than the value of your shares if we had followed the dividend approach.

Moreover, your annual cash receipts from the sell-off policy would now be running 4% more than you

would have received under the dividend scenario. Voila! – you would have both more cash to spend annually and

more capital value.

This calculation, of course, assumes that our hypothetical company can earn an average of 12% annually on

net worth and that its shareholders can sell their shares for an average of 125% of book value. To that point, the

S&P 500 earns considerably more than 12% on net worth and sells at a price far above 125% of that net worth.

Both assumptions also seem reasonable for Berkshire, though certainly not assured.

Moreover, on the plus side, there also is a possibility that the assumptions will be exceeded. If they are, the

argument for the sell-off policy becomes even stronger. Over Berkshire’s history – admittedly one that won’t come

close to being repeated – the sell-off policy would have produced results for shareholders dramatically superior to

the dividend policy.

Aside from the favorable math, there are two further – and important – arguments for a sell-off policy.

First, dividends impose a specific cash-out policy upon all shareholders. If, say, 40% of earnings is the policy, those

who wish 30% or 50% will be thwarted. Our 600,000 shareholders cover the waterfront in their desires for cash. It

is safe to say, however, that a great many of them – perhaps even most of them – are in a net-savings mode and

logically should prefer no payment at all.

20