Berkshire Hathaway 2011 Annual Report Download - page 19

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 19 of the 2011 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.One additional point about these two new arrivals. Both Ted and Todd will be helpful to the next CEO

of Berkshire in making acquisitions. They have excellent “business minds” that grasp the economic forces likely

to determine the future of a wide variety of businesses. They are aided in their thinking by an understanding of

what is predictable and what is unknowable.

************

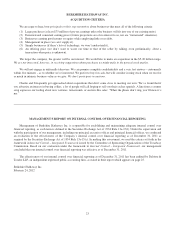

There is little new to report on our derivatives positions, which we have described in detail in past reports.

(Annual reports since 1977 are available at www.berkshirehathaway.com.) One important industry change,

however, must be noted: Though our existing contracts have very minor collateral requirements, the rules have

changed for new positions. Consequently, we will not be initiating any major derivatives positions. We shun

contracts of any type that could require the instant posting of collateral. The possibility of some sudden and huge

posting requirement – arising from an out-of-the-blue event such as a worldwide financial panic or massive terrorist

attack – is inconsistent with our primary objectives of redundant liquidity and unquestioned financial strength.

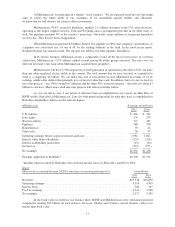

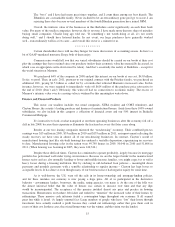

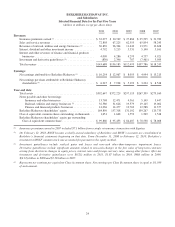

Our insurance-like derivatives contracts, whereby we pay if various issues included in high-yield bond

indices default, are coming to a close. The contracts that most exposed us to losses have already expired, and the

remainder will terminate soon. In 2011, we paid out $86 million on two losses, bringing our total payments to

$2.6 billion. We are almost certain to realize a final “underwriting profit” on this portfolio because the premiums

we received were $3.4 billion, and our future losses are apt to be minor. In addition, we will have averaged about

$2 billion of float over the five-year life of these contracts. This successful result during a time of great credit

stress underscores the importance of obtaining a premium that is commensurate with the risk.

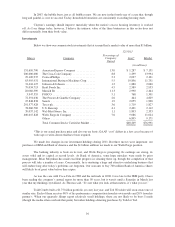

Charlie and I continue to believe that our equity-put positions will produce a significant profit, considering

both the $4.2 billion of float we will have held for more than fifteen years and the $222 million profit we’ve already

realized on contracts that we repurchased. At yearend, Berkshire’s book value reflected a liability of $8.5 billion for

the remaining contracts; if they had all come due at that time our payment would have been $6.2 billion.

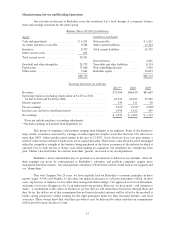

The Basic Choices for Investors and the One We Strongly Prefer

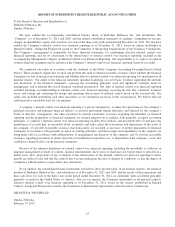

Investing is often described as the process of laying out money now in the expectation of receiving

more money in the future. At Berkshire we take a more demanding approach, defining investing as the transfer to

others of purchasing power now with the reasoned expectation of receiving more purchasing power – after taxes

have been paid on nominal gains – in the future. More succinctly, investing is forgoing consumption now in

order to have the ability to consume more at a later date.

From our definition there flows an important corollary: The riskiness of an investment is not measured

by beta (a Wall Street term encompassing volatility and often used in measuring risk) but rather by the

probability – the reasoned probability – of that investment causing its owner a loss of purchasing-power over his

contemplated holding period. Assets can fluctuate greatly in price and not be risky as long as they are reasonably

certain to deliver increased purchasing power over their holding period. And as we will see, a non-fluctuating

asset can be laden with risk.

Investment possibilities are both many and varied. There are three major categories, however, and it’s

important to understand the characteristics of each. So let’s survey the field.

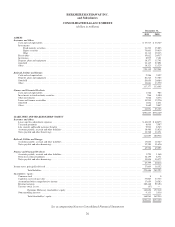

• Investments that are denominated in a given currency include money-market funds, bonds, mortgages,

bank deposits, and other instruments. Most of these currency-based investments are thought of as “safe.”

In truth they are among the most dangerous of assets. Their beta may be zero, but their risk is huge.

Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many

countries, even as the holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal. This ugly

result, moreover, will forever recur. Governments determine the ultimate value of money, and systemic

forces will sometimes cause them to gravitate to policies that produce inflation. From time to time such

policies spin out of control.

Even in the U.S., where the wish for a stable currency is strong, the dollar has fallen a staggering 86%

in value since 1965, when I took over management of Berkshire. It takes no less than $7 today to buy

what $1 did at that time. Consequently, a tax-free institution would have needed 4.3% interest annually

from bond investments over that period to simply maintain its purchasing power. Its managers would

have been kidding themselves if they thought of any portion of that interest as “income.”

17