Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.8

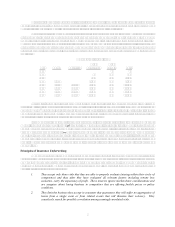

3. They avoid business involving moral risk: No matter what the rate, trying to write good contracts

with bad people doesn’t work. While most policyholders and clients are honorable and ethical,

doing business with the few exceptions is usually expensive, sometimes extraordinarily so.

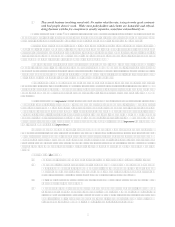

The events of September 11th made it clear that our implementation of rules 1 and 2 at General Re had been

dangerously weak. In setting prices and also in evaluating aggregation risk, we had either overlooked or dismissed

the possibility of large-scale terrorism losses. That was a relevant underwriting factor, and we ignored it.

In pricing property coverages, for example, we had looked to the past and taken into account only costs we

might expect to incur from windstorm, fire, explosion and earthquake. But what will be the largest insured property

loss in history (after adding related business-interruption claims) originated from none of these forces. In short, all

of us in the industry made a fundamental underwriting mistake by focusing on experience, rather than exposure,

thereby assuming a huge terrorism risk for which we received no premium.

Experience, of course, is a highly useful starting point in underwriting most coverages. For example, its

important for insurers writing California earthquake policies to know how many quakes in the state during the past

century have registered 6.0 or greater on the Richter scale. This information will not tell you the exact probability

of a big quake next year, or where in the state it might happen. But the statistic has utility, particularly if you are

writing a huge statewide policy, as National Indemnity has done in recent years.

At certain times, however, using experience as a guide to pricing is not only useless, but actually

dangerous. Late in a bull market, for example, large losses from directors and officers liability insurance (D&O)

are likely to be relatively rare. When stocks are rising, there are a scarcity of targets to sue, and both questionable

accounting and management chicanery often go undetected. At that juncture, experience on high-limit D&O may

look great.

But thats just when exposure is likely to be exploding, by way of ridiculous public offerings, earnings

manipulation, chain-letter-like stock promotions and a potpourri of other unsavory activities. When stocks fall,

these sins surface, hammering investors with losses that can run into the hundreds of billions. Juries deciding

whether those losses should be borne by small investors or big insurance companies can be expected to hit insurers

with verdicts that bear little relation to those delivered in bull-market days. Even one jumbo judgment, moreover,

can cause settlement costs in later cases to mushroom. Consequently, the correct rate for D&O excess (meaning

the insurer or reinsurer will pay losses above a high threshold) might well, if based on exposure, be five or more

times the premium dictated by experience.

Insurers have always found it costly to ignore new exposures. Doing that in the case of terrorism,

however, could literally bankrupt the industry. No one knows the probability of a nuclear detonation in a major

metropolis this year (or even multiple detonations, given that a terrorist organization able to construct one bomb

might not stop there). Nor can anyone, with assurance, assess the probability in this year, or another, of deadly

biological or chemical agents being introduced simultaneously (say, through ventilation systems) into multiple

office buildings and manufacturing plants. An attack like that would produce astronomical workers compensation

claims.

Heres what we do know:

(a) The probability of such mind-boggling disasters, though likely very low at present, is not zero.

(b) The probabilities are increasing, in an irregular and immeasurable manner, as knowledge and

materials become available to those who wish us ill. Fear may recede with time, but the danger

wont the war against terrorism can never be won. The best the nation can achieve is a long

succession of stalemates. There can be no checkmate against hydra-headed foes.

(c) Until now, insurers and reinsurers have blithely assumed the financial consequences from the

incalculable risks I have described.

(d) Under a close-to-worst-case scenario, which could conceivably involve $1 trillion of damage,

the insurance industry would be destroyed unless it manages in some manner to dramatically limit

its assumption of terrorism risks. Only the U.S. Government has the resources to absorb such a

blow. If it is unwilling to do so on a prospective basis, the general citizenry must bear its own

risks and count on the Government to come to its rescue after a disaster occurs.