Berkshire Hathaway 2001 Annual Report Download - page 4

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 4 of the 2001 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

3

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

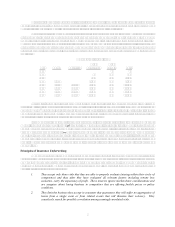

Berkshires loss in net worth during 2001 was $3.77 billion, which decreased the per-share book value of

both our Class A and Class B stock by 6.2%. Over the last 37 years (that is, since present management took over)

per-share book value has grown from $19 to $37,920, a rate of 22.6% compounded annually.∗

Per-share intrinsic grew somewhat faster than book value during these 37 years, and in 2001 it probably

decreased a bit less. We explain intrinsic value in our Owners Manual, which begins on page 62. I urge new

shareholders to read this manual to become familiar with Berkshires key economic principles.

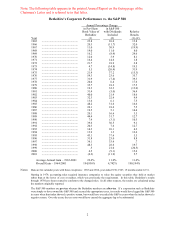

Two years ago, reporting on 1999, I said that we had experienced both the worst absolute and relative

performance in our history. I added that relative results are what concern us, a viewpoint Ive had since forming

my first investment partnership on May 5, 1956. Meeting with my seven founding limited partners that evening, I

gave them a short paper titled The Ground Rules that included this sentence: Whether we do a good job or a

poor job is to be measured against the general experience in securities. We initially used the Dow Jones Industrials

as our benchmark, but shifted to the S&P 500 when that index became widely used. Our comparative record since

1965 is chronicled on the facing page; last year Berkshires advantage was 5.7 percentage points.

Some people disagree with our focus on relative figures, arguing that you cant eat relative performance.

But if you expect as Charlie Munger, Berkshires Vice Chairman, and I do that owning the S&P 500 will

produce reasonably satisfactory results over time, it follows that, for long-term investors, gaining small advantages

annually over that index must prove rewarding. Just as you can eat well throughout the year if you own a profitable,

but highly seasonal, business such as Sees (which loses considerable money during the summer months) so, too,

can you regularly feast on investment returns that beat the averages, however variable the absolute numbers may be.

Though our corporate performance last year was satisfactory, my performance was anything but. I manage

most of Berkshires equity portfolio, and my results were poor, just as they have been for several years. Of even

more importance, I allowed General Re to take on business without a safeguard I knew was important, and on

September 11th, this error caught up with us. Ill tell you more about my mistake later and what we are doing to

correct it.

Another of my 1956 Ground Rules remains applicable: I cannot promise results to partners. But Charlie

and I can promise that your economic result from Berkshire will parallel ours during the period of your ownership:

We will not take cash compensation, restricted stock or option grants that would make our results superior to yours.

Additionally, I will keep well over 99% of my net worth in Berkshire. My wife and I have never sold a

share nor do we intend to. Charlie and I are disgusted by the situation, so common in the last few years, in which

shareholders have suffered billions in losses while the CEOs, promoters, and other higher-ups who fathered these

disasters have walked away with extraordinary wealth. Indeed, many of these people were urging investors to buy

shares while concurrently dumping their own, sometimes using methods that hid their actions. To their shame, these

business leaders view shareholders as patsies, not partners.

Though Enron has become the symbol for shareholder abuse, there is no shortage of egregious conduct

elsewhere in corporate America. One story Ive heard illustrates the all-too-common attitude of managers toward

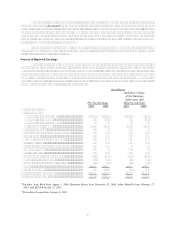

∗All figures used in this report apply to Berkshire's A shares, the successor to the only stock that the

company had outstanding before 1996. The B shares have an ec onomic interest equal to 1/30th that of the A.