Berkshire Hathaway 1999 Annual Report Download - page 9

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 9 of the 1999 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.8

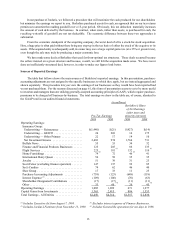

In 1995, GEICO spent $33 million on marketing and had 652 telephone counselors. Last year the company spent

$242 million, and the counselor count grew to 2,631. And we are just starting: The pace will step up materially in 2000.

Indeed, we would happily commit $1 billion annually to marketing if we knew we could handle the business smoothly

and if we expected the last dollar spent to produce new business at an attractive cost.

Currently two trends are affecting acquisition costs. The bad news is that it has become more expensive to develop

inquiries. Media rates have risen, and we are also seeing diminishing returns — that is, as both we and our competitors

step up advertising, inquiries per ad fall for all of us. These negatives are partly offset, however, by the fact that our

closure ratio — the percentage of inquiries converted to sales — has steadily improved. Overall, we believe that our

cost of new business, though definitely rising, is well below that of the industry. Of even greater importance, our

operating costs for renewal business are the lowest among broad-based national auto insurers. Both of these major

competitive advantages are sustainable. Others may copy our model, but they will be unable to replicate our economics.

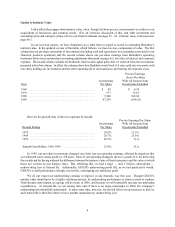

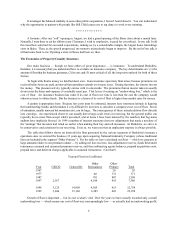

The table above makes it appear that GEICO’s retention of policyholders is falling, but for two reason s

appearances are in this case deceiving. First, in the last few years our business mix has moved away from “preferred”

policyholders, for whom industrywide retention rates are high, toward “standard” and “non-standard” policyholders for

whom retention rates are much lower. (Despite the nomenclature, the three classes have similar profit prospects.)

Second, retention rates for relatively new policyholders are always lower than those for long-time customers — and

because of our accelerated growth, our policyholder ranks now include an increased proportion of new customers.

Adjusted for these two factors, our retention rate has changed hardly at all.

We told you last year that underwriting margins for both GEICO and the industry would fall in 1999, and they

did. We make a similar prediction for 2000. A few years ago margins got too wide, having enjoyed the effects of an

unusual and unexpected decrease in the frequency and severity of accidents. The industry responded by reducing rates

— but now is having to contend with an increase in loss costs. We would not be surprised to see the margins of auto

insurers deteriorate by around three percentage points in 2000.

Two negatives besides worsening frequency and severity will hurt the industry this year. First, rate increases go

into effect only slowly, both because of regulatory delay and because insurance contracts must run their course before

new rates can be put in. Second, reported earnings of many auto insurers have benefitted in the last few years from

reserve releases, made possible because the companies overestimated their loss costs in still-earlier years. This reservoir

of redundant reserves has now largely dried up, and future boosts to earnings from this source will be minor at best.

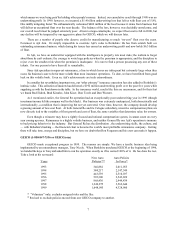

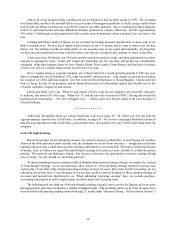

In compensating its associates — from Tony on down — GEICO continues to use two variables, and only two,

in determining what bonuses and profit-sharing contributions will be: 1) its percentage growth in policyholders and 2)

the earnings of its “seasoned” business, meaning policies that have been with us for more than a year. We did

outstandingly well on both fronts during 1999 and therefore made a profit-sharing payment of 28.4% of salary (in total,

$113.3 million) to the great majority of our associates. Tony and I love writing those checks.

At Berkshire, we want to have compensation policies that are both easy to understand and in sync with what we

wish our associates to accomplish. Writing new business is expensive (and, as mentioned, getting more expensive).

If we were to include those costs in our calculation of bonuses — as managements did before our arrival at GEICO —

we would be penalizing our associates for garnering new policies, even though these are very much in Berkshire’ s

interest. So, in effect, we say to our associates that we will foot the bill for new business. Indeed, because percentage

growth in policyholders is part of our compensation scheme, we reward our associates for producing this initially-

unprofitable business. And then we reward them additionally for holding down costs on our seasoned business.

Despite the extensive advertising we do, our best source of new business is word-of-mouth recommendations from

existing policyholders, who on the whole are pleased with our prices and service. An article published last year by

Kiplinger’s Personal Finance Magazine gives a good picture of where we stand in customer satisfaction: The

magazine’s survey of 20 state insurance departments showed that GEICO’s complaint ratio was well below the ratio

for most of its major competitors.

Our strong referral business means that we probably could maintain our policy count by spending as little as $50

million annually on advertising. That’s a guess, of course, and we will never know whether it is accurate becaus e

Tony’s foot is going to stay on the advertising pedal (and my foot will be on his). Nevertheless, I want to emphasize

that a major percentage of the $300-$350 million we will spend in 2000 on advertising, as well as large additional costs